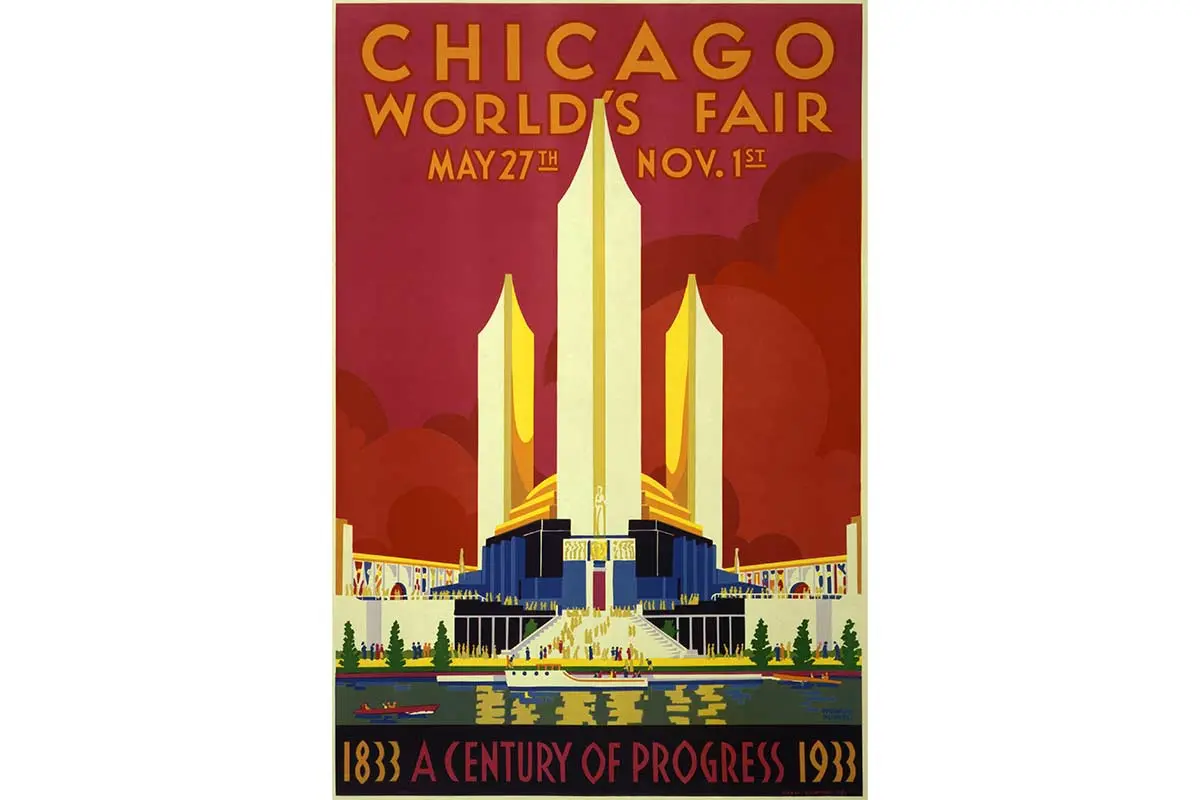

A Century of Progress International Exposition

The 1933 World’s Fair opened during the Great Depression when times were tough. One-quarter of America’s work force was unemployed. Those lucky enough to still be working had seen their wages plummet by 42 percent since 1929. Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany on January 30 of that year, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) on March 4. It was the time of Prohibition. Chicago was known for organized crime and political corruption.

The organizers of the Fair wanted to change the world’s perception of the city of Chicago. They did that, and more. Much more. The Fair created tens of thousands of jobs, attracted 48 million visitors, and offered optimism and hope to a depression-weary country.

Origins

In 100 years, Chicago had grown from a small wilderness settlement on the western frontier, to the fifth largest city in the world. Initially designed to celebrate the past, “A Century of Progress International Exposition” evolved into an entertaining and educational event showcasing a tech-driven future. It opened May 27, 1933, on land along the shorelines of Lake Michigan. Stretching from 12th to 39th streets, the fairgrounds covered 430 acres on Northerly Island, Burnham Park, and included the area of present-day McCormick Place.

In 1926, Charles G. Dawes (Vice President of the U.S., a former General and Nobel Prize winner) wanted to produce a World’s Fair to celebrate his adopted hometown. He recruited his brother Rufus, a successful financier, and Lenox R. Lohr. The three brought a military and industrial organizational framework to the Fair. Dawes wanted some changes from previous events: he thought it should be privately financed, that it should foster cooperation, and that it should make a profit.

Trains, taxis, and buses delivered visitors to one of six entrances. Drivers arrived at “the world’s largest parking lot.” Admission to the Fair was 50 cents, and most entered near the 240-foot tall, 3,000 neon-tube-lit Havoline Thermometer. Greyhound buses, roller chairs, and rickshaws offered rides around the expansive grounds. Unlike previous events, specific areas of interest were intermixed. Education, science, entertainment, business, carnival attractions, and commerce overlapped side by side.

Attractions

There were corporate pavilions, carnival games, science halls, thrill rides, freak shows, kid rides, infant incubators, biplanes, boat races, swimming races, diving exhibitions, games of chance, foreign villages, gardens, sculptures, submarine tours, seaplane rides, nighttime entertainment, and roaming geese and deer. Unlike 1893, this Fair boasted not one, but two Midways. Across the water the Beach Midway offered a double Ferris Wheel, the Devil’s Playground, the Tower Dip, and the Enchanted Island. The “Main Midway” housed replicas of the 1833 DeSaible Cabin and the five historic homes of Abraham Lincoln. The biggest attractions were the commercial areas.

The Belgian village replicated a Flemish village in the 16th century, with shops, restaurants, and a church. Vistors could buy food, flowers, and photographs. The Spanish Pavillion sold tour packages. The Moroccan Village offered a variety of coffees and teas. The “Indian Village” showed stunt horseback riding, demonstrated archery and tomahawk tossing, and merchants sold rugs, jewelry, and toys. Visitors could pay for pictures with camels at the Oriental Village. The Olde Heidelburg Inn offered food (and beer in 1934).

The Hollywood Showcase demonstrated how movies and radio shows were made. A wild west show with gun fights competed for visitors, alongside a gorilla village, a log rolling contest, and Frank Buck’s wild animal exhibit. The “Midget Village” was one of the biggest money-making areas, a miniature city with 45 buildings and a population of about 100 people.

Yet, nothing at the “Main Midway” compared with the Streets of Paris. It had cafes, restaurants, shops, mimes, street dancers, musicians, flags, French signs, fake gendarmes, peep shows, scantily clad dancers, and Sally Rand and her fan dance—the most successful act of the Fair, at times grossing a $100,000 a day. Rand is a great success story of perseverance, entrepreneurship, and imagination. A successful actress during the silent film era, she appeared in over 20 movies. She worked with Humphrey Bogart in summer stock, and Cecil B. DeMille gave her, her stage name. Unfortunately, she had a slight lisp and rarely worked in the talkies. Reinventing herself, Rand imagined and promoted her nude-appearing fan dance. She started at $90 a week (the equivalent of $2,230 in 2025).

The Fair did not make a profit, and the decision was made to extend it into a second season. Prohibition ended December 5, 1933. The 1934 fair offered alcohol in the Midway, and that boosted revenues. Ice skating was available that summer, and more villages were added. Rand moved from Paris to the Italian Village and exchanged her fans for bubbles. For the last 11 weeks of the 1934 season, Rand made a $1,000 a week (almost $25,000 weekly, today).

The “Sky Ride” connected the two midways and offered visitors views previously seen only from hot air ballon rides or from an airplane (an experience then unknown to most). A total of five companies combined to create the $1.4 million structure. Like the Ferris Wheel, it was not completed by show opening, but what an engineering feat it was. Over 100 miles of cable, and four million pounds of steel connected the twin 638-foot-tall towers. There were two rocket-shaped cars that shuttled 36 passengers across the water. About one out of every eight visitors paid to experience the thrilling view. It was new tech, and there were no major incidents.

Businesses

Businesses played a crucial role at this Fair as they had done in fairs past. They paid for the privilege to be there. The paid for the displays, and in some cases, they built massive, architecturally impressive structures. Their demonstrations attracted fairgoers, and their products foreshadowed the future.

Dawes wanted to save costs by fostering cooperation. By design, multiple groups exhibited in a single building. Examples included: the 400,000 square foot Hall of Science; the Food and Agricultural Building; and the Hall of Religion. The Travel and Transportation building displayed trains, stagecoaches, early automobiles, “Dream Cars of the Future,” and airplanes. The colorful art-deco, tri-towered US Federal building housed exhibits from 21 states. Multiple businesses in The Home and Industrial Group displayed new materials and designs. The House of Tomorrow provided a future look at construction and appliances; it showcased large glass panes, an open floor space, air conditioning, and an airplane hangar. The Electrical Building housed 20 companies offering displays of new and existing products.

Many corporations chose to compete separately. General Electric (GE), Westinghouse, AT&T, A&P, Heinz, Sears and Roebuck, and Johns-Manville all presented products in their own pavilions. Schiltz, Miller, and Pabst sponsored restaurants in 1933 and sold beer in ‘34. IBM displayed over 700 items. RCA demoed an early TV, and broadcasted radio programs including World Series games. The biggest, the most popular displays, and some of the most striking architecture centered on transportation.

Sinclair Oil debuted their new trademark: a giant, green brontosaurus. Inside their building, seven animated dinosaurs lunged at each other as they roared and growled. Firestone attracted visitors by demonstrating how tires were made, starting with hot, molten rubber. Goodyear flew two blimps; for a $3 fee, one could take a 15–20-minute air ride.

The General Motors 131,000 square foot building had a 177-foot tower and two exhibit halls. Showcasing several brands, the highlight was a fully functioning assembly line. Chevrolets were produced on-site, driven out of the building, and paraded around the Fairgrounds. Visitors could order a specific car, watch it being manufactured, and drive it home at the end of the day. (Of course they had to pay for it). Car giveaway contests were held.

The Chrysler pavilion had an exhibit hall, a 125-foot tower, and an adjacent racetrack. Chrysler showed brands and demonstrated pre-assembly performance checks. Outside, the “Hell Drivers” raced cars, performed stunts, and even flipped them on their sides to prove the vehicle’s strength and durability.

Ford Motor Company did not have a presence that first year, but after seeing the attendance at the General Motors Pavilion, Henry Ford spent $2.5 million on exhibits and employed over 800 people for the 1934 show. Ford had four different exhibits totaling 137,000 square feet of space.

The World

International involvement was limited due to the world-wide Depression. Only 19 countries officially participated (the foreign villages at the Midway were independent commercial enterprises, not sponsored by any government). Italy showcased exhibits featuring Guglielmo Marconi and the radio; they also housed a popular restaurant. China presented elaborately costumed dancers, musicians and artists. Sweden, Czechoslovakia, and Japan also attracted crowds.

Legacy

According to a New York Times article, the Fair cost $38.7 million in 1933—that would be the equivalent of $960 million today. At the end of the second year, after paying off the investors, the Fair had generated a profit of $4 million (in today’s money). The Fair provided a blueprint for a privately funded, profitable event. Architecturally, it trended from Art Deco to Art Moderne. It offered optimism for the future and demonstrated the resiliency of the American people. The Fair closed on Halloween with costumes, looting, and fighting.

This story originally appeared as a truncated version in the Q4 2025 issue of Exhibit City News, p. 86. For original layout, visit https://issuu.com/exhibitcitynews/docs/exhibit_city_news_-_oct_nov_dec_2025/86.