In 1890, the population of the state of California was 1.9 percent of the United States. Over the next 30 years, the number of people in the state tripled, and, by 2020, California would be 12 percent of the total population of the country. The gold rush of 1849 started the migration west; but it was two international expositions in San Francisco that showcased the state to 20 million people and planted the seed for innovation and growth.

Lighting the Way

1894 The California Midwinter International Exposition, held January 27 through July 5, was the first World’s Fair to open in the middle of winter and the first to be held west of the Mississippi. The fair was the brainchild of Michael H. de Young,

the founder and publisher of the San Francisco Chronicle.

A National Commissioner for the 1893 Chicago’s World’s Fair, de Young travelled east to Chicago as the financial Panic of 1893 spread west. People lost jobs and banks failed across the country, including in San Francisco. By 1894, unemployment nationwide would climb to 18 percent and the depression would last until 1897.

In May of 1893, as millions of people streamed onto the Chicago Fairgrounds, and tens of thousands viewed the California exhibit, de Young wondered if a similar fair could bring people and jobs to his hometown. His main concern: Chicago had years to plan, construct, and sell space in the exposition; he had seven months. Funding for the fair proved to be no problem. Convincing exhibitors onsite in Chicago to come to California was also an easy sell—it was a new market, the weather would be beautiful, and de Young offered to pay the shipping costs from Chicago to San Francisco for many of international exhibitors that committed to the show. One unexpected hurdle, however, was the controversy over the site location and the battle to build in Golden Gate Park. Groundbreaking did not begin until August 24. Amazingly, the Fair opened five months later, with pre-show festivities starting on January 15.

Situated on 200 acres, the exposition attracted over two million people, with businesses from 38 nations, five states, and 36 California counties. Defying the depression, the exposition brought dollars and jobs to the area. It employed several hundreds of thousands of people (including construction personnel and the staff working the show) and the event made a profit of $66,851. Companies displayed textiles, machinery, mining equipment, bicycles, shoes, fruit, furniture, clothing, crystal, and pottery.

In Chicago, de Young could not convince George Ferris to move his giant Ferris Wheel west, but a member of the California delegation volunteered to design and build a similar, but smaller, attraction: J Kirk Firth’s Wheel had sixteen cars, each rotating 10 people 120 feet into the air.

In 1894 electricity was still a relatively new phenomenon. The illuminated silhouette of the expo at night was unlike anything previously seen in California. Two of the more memorable attractions were the Electric Fountain and Bonet’s Electric Tower.

The Electric Fountain had water that shot 90 feet upwards and was floodlit by colored lights from below.

Bonet’s Electric Tower was a steel structure, 272 feet high, housing the most powerful searchlight in the world. It was a third the size of the Eiffel Tower and at night, the tower blazed with the light of 3,200 sparkling incandescent bulbs. An electric elevator carried passengers to three observation areas, stopping at 91 feet, 147 feet, and 210 feet. The searchlight atop the tower was so bright that one reporter wrote, he “could read a newspaper at midnight ten miles away.”

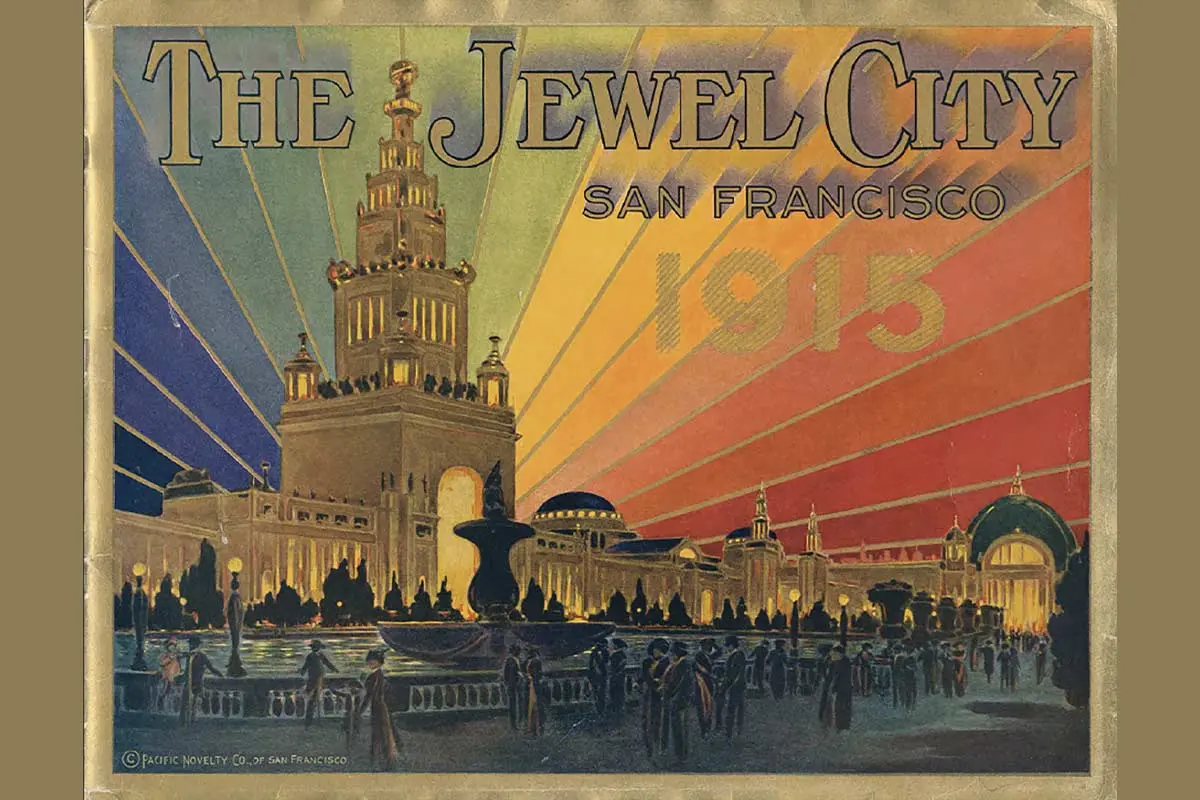

Showcasing “The Jewel City”

1915 The Panama-Pacific International Exposition is often overlooked and underappreciated, although it is one the five most impressive World Fairs in U.S. history. It hosted 28 countries, 32 states, and attracted almost 19 million visitors, at a time when war pummeled Europe. The show celebrated the building of the Panama Canal and the rebuilding of San Francisco after the devastating 1906 earthquake. The site of the exposition covered “a mudhole with a view,” located in an area now known as the Marina District. The place was a 10-month mini-metropolis, two and half miles long, a half mile wide, and covering 435 acres. The entrance to the fair was adjacent to The Jewel Tower—a 450-foot-tall structure, with 125,000 faceted pieces of glass and tiny mirrors. These glittering “jewels” moved with the wind, twinkling day and night.

The show had something for everyone: celebrities, daredevils, culture, history, sculptures, scientific lectures, women’s studies, technology, innovations, 300 parades, and 2,000 concerts. It showcased car, camel, horse, aeroplane races; nighttime aerial displays; military and baby parades; and dog shows. It had lagoons, Japanese tea gardens, the original Liberty Bell, and the single largest collection of fine arts in the world. There were exhibits, displays, pavilions, and over 80,000 products. There was so much to see, it was said, people “walked until their feet hurt.”

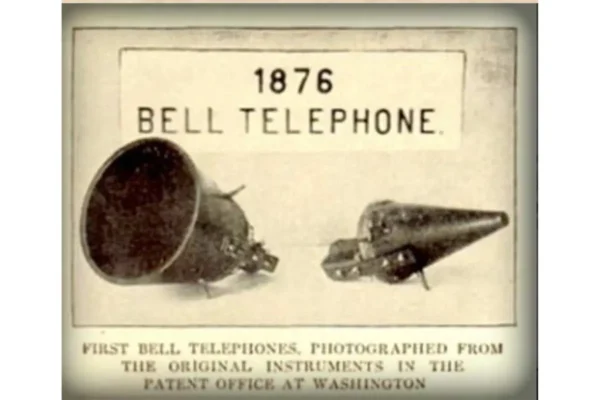

The first long distance, intercontinental phone call occurred on January 15th, with a reenactment of the original connection between Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas Watson. Only this time, almost 40 years after the first successful call, instead of being in adjacent rooms at the same laboratory, Watson was in San Francisco and Bell in New York City. Subsequent intercontinental calls had people in New York listening to the live sounds of the Pacific Ocean and New Yorkers reading local newspapers to fairgoers.

Exhibiting companies included: International Harvester; Waltham Watch; Hearst (demonstrating the largest color printing press in the world: a two-story press capable of producing over one million newspaper pages an hour); Sperry Flour (with international chefs cooking and offering free tastings); US Steel; Kodak (displaying two-color Kodachrome photographs); Union Oil (which became Unocal 76 and was acquired by Chevron in 2005); Columbia Graphophone Co. (which became EMI and Columbia Records). The Underwood Typewriter company displayed an enormous working typewriter: a machine twenty-one feet long, fifteen feet high, and weighing fourteen tons. GE (showing “The Home Electrical”), Heinz, and Westinghouse were there, with motion pictures entertaining audiences in their pavilions.

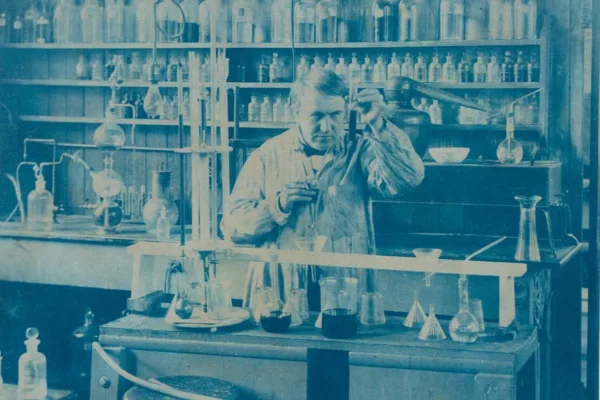

Henry Ford constructed a working factory, where exposition attendees could watch a single car being assembled every 10 minutes—18 Model Ts in three hours, every day, Monday through Saturday. Upon completion, the cars were driven out of the building and paraded around the fairgrounds. Thomas Edison worked on his friend’s assembly line one afternoon, unnoticed by the public.

Second in popularity to the temporary Ford factory was a five-acre working replica of the Panama Canal. Foreshadowing future amusement park rides, there was a moving platform which transported seated visitors around the “canal” as they listened to recorded messages via telephone receivers.

Other popular attractions included: a working Levi factory, an automated U.S. Post Office, and an incubator pavilion. Santa Fe Railroad displayed a replica of the Grand Canyon. Union Pacific built a miniature Yellowstone Park, complete with working geysers. Both railroads promoted travel and sold tours. Finally, for entertainment in the fair’s amusement area, “The Zone,” there was the “Aeroscope”—“a long metal arm terminating in a two-story house and capable of lifting 120 people 265 feet in the air.”

The exposition was open from February 20–December 4, 1915. It made a profit of $2,401,911.

In a 150 years, 75 percent of all international expositions failed to make a profit, but these first two San Francisco shows made money. Between 1915 and 1940, four more World’s Fairs occurred in California, including another in San Francisco. These combined events attracted over 30 million attendees. Like conventions today, these expositions created jobs, stimulated the economy, and promoted their hometowns—but none equaled the grandeur, nor the success, of the 1915 show.

What was the legacy of the Pan-Pacific Exposition?

To quote Burton Benedict, a former Dean at UC Berkley, “It celebrated the rebuilding of San Francisco; it asserted the importance of California and the American West; it turned American attention toward the Pacific and South America.”

It can also be argued that the technology and innovation of Silicon Valley today, started with the World’s Fairs in San Francisco.

Tradeshows Today – Still Bringing in Business

Four convention centers in California have exhibit floors with a half million to more than a million square feet of space: Moscone, San Diego, Los Angeles, and Anaheim. In 2019, tradeshows and business events in the state supported 329,000 jobs and generated an economic impact of $41.1 billion.

Tradeshows work. They work very well!

This story originally appeared in the Q4 2024 issue of Exhibit City News, p. 74. For original layout, visit https://issuu.com/exhibitcitynews/docs/ecn_q4_2024/74.