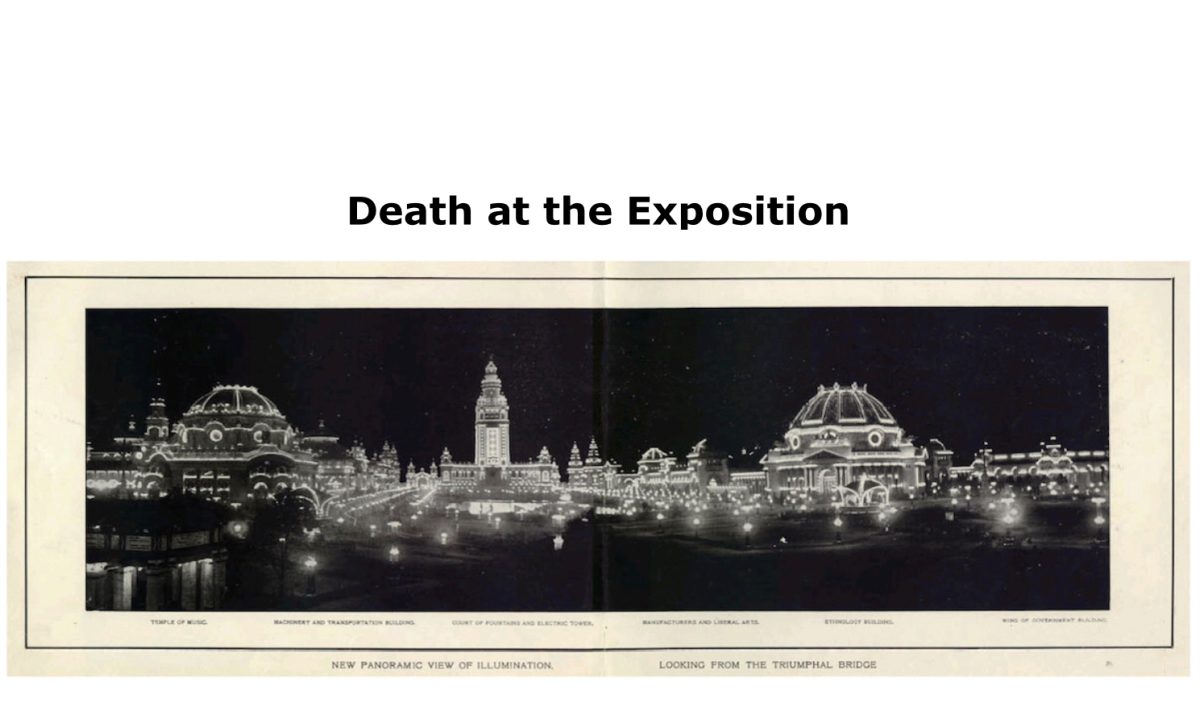

The Pan-American Exposition, Buffalo New York, May 1-November 2, 1901.

In the end, it seemed almost inevitable: the problems with the fair, the assassination, the aftermath; everything. But in the beginning … it was all hope … optimism … and the promise of a bright future.

THE CITY OF LIGHT

It started with the energy and excitement of the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. The anticipation increased when Westinghouse began building generators for the proposed Niagara Falls power plant. Buffalo wanted the thrill, the brand recognition, and the revenues that a World’s Fair would bring. In 1895, the city’s elite travelled to Atlanta for the “Cotton States and International Exposition”; once there they announced plans for an 1899 World’s Fair in Buffalo. However, two years later at the Nashville Centennial, they changed the date to1901, and decided to welcome only businesses from the western hemisphere – hence the name, “The Pan-American Exposition”.

Buffalo was the 8th largest city in the country in 1900 (population 352,387); and over half of the country’s populace was within a day’s travel by rail. Thanks to the Niagara power plant,the town had street lamps everywhere. Nicknamed, “The City of Light,” Buffalo was primed for a World’s Fair: It had the space; it had the transportation; it had the desire; it had the electrical power; and it would have the President of the United States. They expected between ten and twenty million attendees.

“’The Pan’” they said, “could not fail.”

THE PLANNED EXPOSITION

Covering 350 acres, five miles from downtown and twenty–five miles from Niagara Falls, the Exposition would display the newest scientific, technological, and material accomplishments of the day. Nineteen countries would attend. Thousands of companies planned to exhibit. Hundreds of businesses with brand names still recognizable today, signed up to sell their products.

Buffalo wanted to outshine Chicago’s Fair, and planned their buildings to be brighter, more electrifying, and more colorful (“The Rainbow City” vs “The White City”). To entice attendees, they offered free food, free drinks, and free souvenirs (some of the time).Buffalo’s Midway had concerts, foreign villages, the “House Upside Down”, and “Cleopatra’s Temple”. To replace Chicago’s Ferris Wheel, Buffalo designed a giant 140-foot-long see-saw,elevating to 275 feet in the air, with two spinning cages, each carrying 72 passengers. The expectation was, the Pan-Am would be the best Exposition in the United States in the last fifty years.

But, if one was observant, there were multiple signs that it wouldn’t be all sunshine and rainbows: (1) pre-show funding was significantly less than projected; (2) the architects and event planners did not communicate expectations; (3) there were work stoppages due to strikes, and weather delays (including a heavy blizzard ten days prior to show opening); (4) construction was not completed on time; (5) initial attendance numbers were considerably lower than predicted; and (6) what didn’t seem important at the time, the First Lady took sick in June, thereby forcing the postponement of the President’s scheduled speech until September.

THE PRESIDENT’S VISIT

President William McKinley planned a two-day visit to the Exposition. On day one, he would deliver a major policy speech. The second day, he would tour the relatively new power plant at Niagara Falls, and then do a hand-shaking meet-and-greet back at the Fair, inside the “Temple of Music”.

McKinley delivered his address on September 5, 1901. A Pan-Am record-setting crowd of 116,000 people attended that day. The President spoke on trade reciprocity, and ending American isolationism. It was said to be one of his finest speeches. He also gave one of the great summations concerning the efficacy of events:

“Expositions are the timekeepers of progress. They record the world’s advancement. They stimulate the energy, enterprise, and intellect of the people; and quicken human genius. They go into the home. They broaden and brighten the daily life of the people. They open mighty storehouses of information … Who can tell the new thoughts that have been awakened, the ambitions fired, and the high achievements that have been wrought through this exposition.”

The President’s personal secretary, George Cortelyou, was concerned about a possible assassination attempt and twice removed the September 6th Temple of Music visit from the itinerary. The President insisted on meeting his public, however, saying “Why should I (cancel)? No one would wish to hurt me.” (What no-one knew at the time, an anarchist was in fact planning to assassinate the President. Taking advantage of the rescheduled visit, the assassin moved to Buffalo August 31; he purchased a .32 caliber Iver Johnson revolver on the third of September; he tried to approach the President on the day of the speech, but could not get close enough to do him any harm).

On the morning of September 6, the President and his wife breakfasted and briefly visited the Exposition. Then, he, Pan-Am President John Milburn, and the fair’s Chief Medical Doctor, Roswell Park, travelled to tour Niagara Falls, and the power plant. Park, the Chief Trauma Surgeon in Buffalo, and a proponent of antiseptic practices, stayed behind in Niagara Falls for a scheduled surgery that afternoon, as McKinley headed to the Temple of Music. Had Park stayed with McKinley, perhaps his life could have been saved.

THE SHOOTING

September 6, 1901 was hot day in Buffalo; and somepeople used handkerchiefs to wipe their sweaty brows. The assassin had a white cloth in his hand, not to wipe his face, but to conceal a handgun. At 4:07 PM, two shots rang out in quick succession. One bullet deflected off a coat button and caused a superficial chest wound. The second bullet entered the President’s stomach. A third shot was prevented by the heroic actions of James Parker, a tallwaiter standing in line to meet the President. Parker knocked the pistol out of the assassin’s hand, and pushedhim to the floor – all before the stunned 75-person security force reacted.

Artist rendering by T. Dart Walker

The ambulance arrived in six minutes. Instead of being rushed to Buffalo’s General Hospital, the Presidentwas taken to the Emergency Hospital on the Fairgrounds.It was closer, but not as well–equipped. The best surgeon in the city, Dr. Park, was unavailable. Instead of a doctorexperienced with both gunshot and abdominal wounds, a gynecologist, Dr. Mathew Mann, performed the surgery.

There was no electricity in the room. The doctor operated with the waning sunlight being reflected off a metal bedpan. Mann could not find the bullet; he removed some cloth from the wound, probed with his unglovedfinger, then sewed up the President, without first draining the incision. It was neither sterile nor sanitary. (Ironically, one of the inventions displayed at the Exposition was an x-ray machine; it had been developed six years earlier, but was not used during the operation, nor later, during the recovery).

The operating room at the Exposition’s Emergency Hospital

While initially appearing to improve, McKinley was 58, overweight, and his wounds had not been cleaned. Gangrene set in and was poisoning his blood. McKinley fought during the Civil War; he enlisted as a private, and through battlefield promotions, was discharged as a major; he survived bloody Antietam; he survived having a horse shot from under him; but he would not survive this battle.

THE AFTERMATH

A week after being shot, President McKinley died at 2:25 AM on September 14. Some would say it wasn’t the bullet that killed McKinley, rather it was the lack of proper medical attention. Others say, the single bullet not only killed the President, but also killed Buffaloas well.

With McKinley’s death, the bright lights of the fair began to fade. At Expositions in the past, attendance would increase dramatically during the final two months. But at the Pan–Am, daily attendance peaked on September 5. Initially some fair–goers visited the Emergency Hospital, a macabre tourist attraction, but overall attendance steadily declined. By mid-October it was clear the fair had severe financial problems: expenses exceeded revenues by more than a 2:1 margin. (While total attendance was recorded as 8,120,048, the total paid attendance would prove to be only 5,306,859). The Exposition closed the afternoon of November 2, still owing contractors millions. The next spring, the Fairgrounds were demolished. Some city leaders moved away that year; others stayed but invested their fortunes elsewhere. John Milburn, the President of the Fair, and in whose house McKinley died, left his law practice and moved to New York City in 1904.

In 2022, the population of Buffalo was 276,807, and the city’s rank nationwide dropped seventy spots from 1900, from the 8th to the 78th largest city in the country.