by Bob McGlincy, director, business management at Willwork Global Event Services

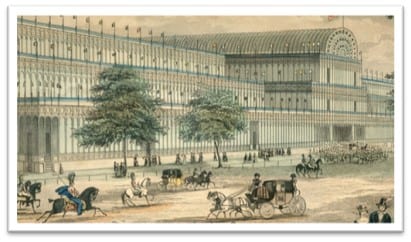

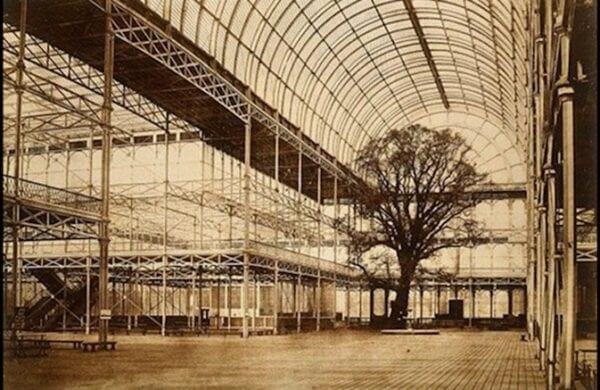

“The Crystal Palace,” home to The Great Exhibition of 1851, was a glittering glass and iron structure, with 990,000 square feet of exhibit space. It was 1,850 feet long, 408 feet wide; and at 128 feet high, it was tall enough to enclose existing trees within the interior of the building. Despite its massive size, the Crystal Palace was an I&D project: the building was designed as a temporary structure; it was partially pre-fabricated; it was modularly built; it had very tight time constraints that had to be completed before show opening; it was dismantled after the show and then shipped to a new location. It’s “the biggest ‘I&D’ project in the history of the world” due to its size, and because of the historical significance of both the show and the building itself.

“The Crystal Palace,” home to The Great Exhibition of 1851, was a glittering glass and iron structure, with 990,000 square feet of exhibit space. It was 1,850 feet long, 408 feet wide; and at 128 feet high, it was tall enough to enclose existing trees within the interior of the building. Despite its massive size, the Crystal Palace was an I&D project: the building was designed as a temporary structure; it was partially pre-fabricated; it was modularly built; it had very tight time constraints that had to be completed before show opening; it was dismantled after the show and then shipped to a new location. It’s “the biggest ‘I&D’ project in the history of the world” due to its size, and because of the historical significance of both the show and the building itself.

The Great Exhibition opened on May 1, 1851. It was one of the defining moments of the Victorian era, and it presented the blueprint for successful expositions for the next 168 years. The building would influence thousands of future designs. But, at 12 months prior to show opening, there was no design, no land, no consensus and no money for the project.

Countdown to the Exhibition

May 1850: Members of Parliament, and much of the press, did not want an international exhibition. For months they expressed their concerns and fears—concern that a permanent building would ruin the looks of the park; concern the Exhibition would attract too many people; concern the crowds would be rowdy; fear the crowds would destroy the Park; fear the crowds might riot and attack Parliament; fear foreigners might spread disease; fear of a new plague.

The “Royal Society Executive Building Committee” had sent RFPs earlier in the year. By mid-May, they had received and rejected 245 architectural proposals. The committee then created a “group design.” The public hated that design; and the committee had a major problem: the dates of the show had already been announced.

June 9, 1850: Joseph Paxton walks the grounds of Hyde Park. He imagines a giant greenhouse would solve many of the potential problems. It could be temporary. It could be modular, pre-fabricated and built quickly. The biggest challenge, however, is the size. Paxton has already built the biggest glass building in the world; however, what was needed would have to be 30 times larger!

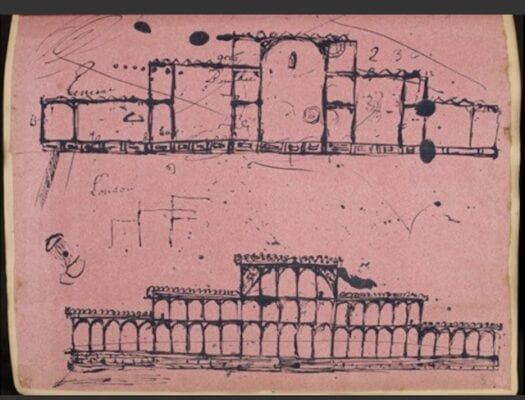

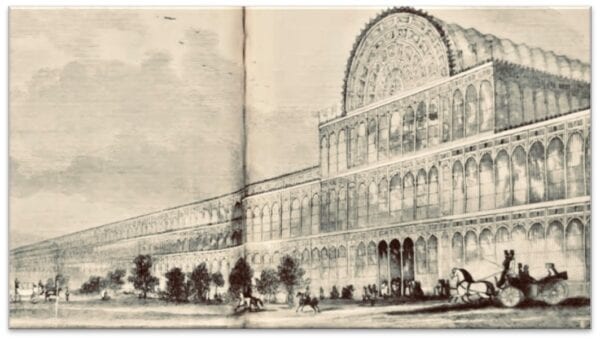

June 11, 1850: In addition to his duties as head gardener, Paxton is a director of the Midland Railway Company; and during a board meeting, he doodles a rough preliminary sketch (pictured right). It is a glass and metal modular design for a giant greenhouse. It would be cheaper, faster and larger than any of the structures previously proposed.

Mid-June: Paxton’s design meets with resistance from members of the building committee. “He’s not an architect.” “He’s a mere gardener.”

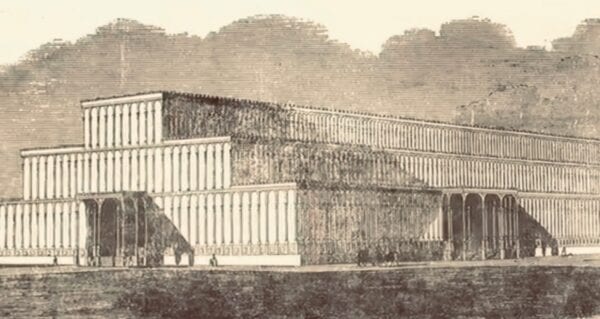

June 21: Paxton takes ten days to develop ideas. He creates a more finished rendering. He talks with Charles Fox (of Fox-Henderson, with whom he has worked previously) for costs and construction concerns. He works the numbers. Still the committee pushes back on the design.

July 6: Paxton decides to force the issue. He has his new rendering published in the Illustrated London News. The public loves the design. Under pressure, the committee realizes it is running out of time. And out of options.

July 15: The Commission decides to accept Paxton’s design, but says the final proposal must be due in 11 days—which includes construction drawings, all costs and final numbers.

Friday, July 26, 1850: Paxton meets the deadline. The bid of 150,000 pounds is verbally accepted. The contract would not be signed until October. Paxton and Fox-Henderson have no choice, however. If they are to build a structure in time for the show, they have to start immediately.

Nine Months and Two Days to Show Opening

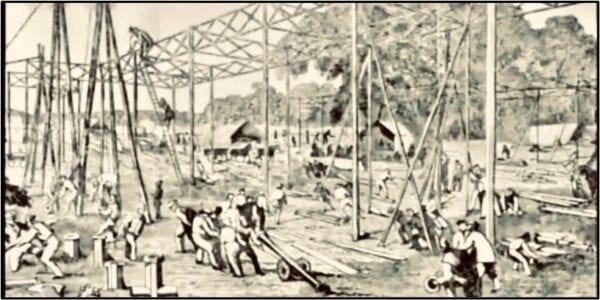

Tuesday, July 30, 1850: Preliminary work begins with 30 men the first week. They plot the land, begin to level the foundation area, and lay out locations for bases for the columns. Starting the following week, crews will work Monday through Saturday, every week, until the show opens.

Paxton’s and Fox’s plan was to control labor numbers, and thereby control the cost of the build.

August: A perimeter fence of approximately 30,000 square feet is installed. The daily crew size in August ranges from 43 to 60 men. Initial materials begin to arrive. The building will need 4,500 tons of iron, 1,000 iron columns, 2,224 trellis girders, 30 miles of gutters, 202 miles of sash bar, 60,000 square feet of lumber, 293,655 panes of glass, and 16 very large laminated timber arches (the semi-circular ribs of the transept). Materials are transported by train to London, then loaded onto horse-drawn wagons, and hauled to the construction site at Hyde Park.

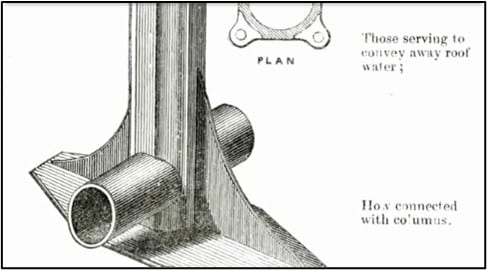

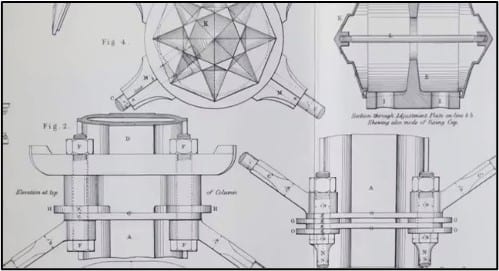

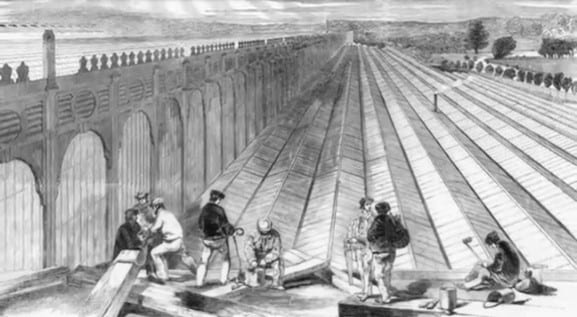

From his experience building greenhouses, Paxton had designed an innovative ridge and furrow system with hollow iron columns for drainage. He believed he had a “kit of parts” (pictured right) which would make design and assembly easier and quicker. In some ways, constructing the Crystal Palace was like building a giant erector set. Or, more precisely, assembling a huge systems exhibit.

From his experience building greenhouses, Paxton had designed an innovative ridge and furrow system with hollow iron columns for drainage. He believed he had a “kit of parts” (pictured right) which would make design and assembly easier and quicker. In some ways, constructing the Crystal Palace was like building a giant erector set. Or, more precisely, assembling a huge systems exhibit.

September: Off site, materials continue to be produced, and modules start to be assembled. On-site, construction crews increase from 56 a day to 293 by the end of the month.

September 14. First delivery of cast iron columns.

September 26: Erection of columns begins; the first girder goes up. The frame will take nine weeks to complete. There were many benefits to a partially pre-fabricated bulding: The parts could be cheaply mass produced off-site in large quantities. Assembly was quick; and the structure easy to erect. Its lightweight meant there was relatively little need for heavy machinery.

October: Crews increase from 467 a day the first week to to 841 a day the last week.

Six Months to the Show

Six Months to the Show

November: The daily crew size increases from 1,538 the first week to 2,129 at the end of the month.

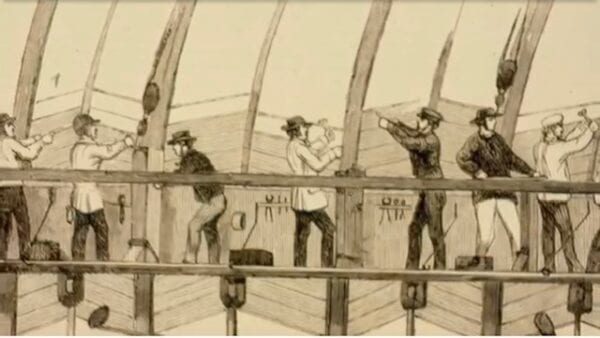

November 2. Glazing starts; construction of the frame continues; 293,653 indivi dual panes of glass were installed. Each pane of glass is 10” wide x 48” long. Each module, in fact everything, was scaled to these dimensions. The entire exterior surface could be glazed using identical panes; this reduced production costs as well as installation time and labor.

dual panes of glass were installed. Each pane of glass is 10” wide x 48” long. Each module, in fact everything, was scaled to these dimensions. The entire exterior surface could be glazed using identical panes; this reduced production costs as well as installation time and labor.

A crew of 80 glaziers installed 18,000 panels the first week. If they can keep that pace up, the scheduled completion date would be March 1, 1851 – two months prior to show opening. But still the interior must be finished, the hall prepped and the show moved in.

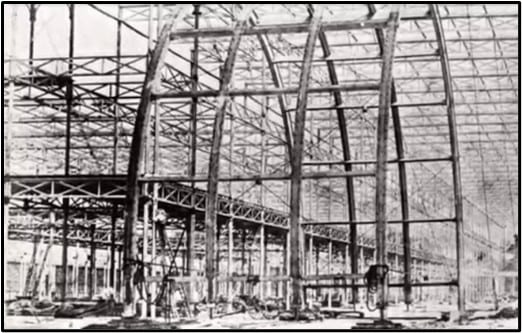

November 28: Except for the transept, the exterior frame is complete. While the glazing is started, it will need to continue for months. The arches still need to be raised, although that will be surprisingly quick. A lot of work still needs to be completed on the interior—and that does not include the flooring, the banners, the fountains, the freight or the exhibits.

November 28: Except for the transept, the exterior frame is complete. While the glazing is started, it will need to continue for months. The arches still need to be raised, although that will be surprisingly quick. A lot of work still needs to be completed on the interior—and that does not include the flooring, the banners, the fountains, the freight or the exhibits.

December: Crews vary from 2,128 a day to 2,035. There is one death, a carpenter falls from the scaffolding. Two other injuries occur that month. These three are the only ones reported for the enti re project.

re project.

December 4: The first arch is raised. The semicircular arch ribs were made of laminated timber, and it took one week to install all 16 arches.

December 11: The building frame is completed. Punch, a weekly British magazine, likes the light and airy look, and calls the structure a “Crystal Palace.” This is the same magazine that, in July, called the rendering, “an example of an early English shed.”

Four Months to Show Opening

January: Labor goes from 2,145 the first week down to 1,417 at the end of month. But the labor call will increase to 2,128 in April. The installation of the glass continues, sped on by another Paxton labor-saving device (a trolley, pictured left).

February: Paxton and Fox continue to control the labor call; it averages 1,285 a day for the month. After the roof was completed, portions were tarped to keep the sun and heat out. The interior of the South Hall was paneled in wood, also to lessen the effects of the greenhouse heat. The fencing around the perimeter of the building is removed. The boards are recycled, and become the interior flooring. The boards are spaced about 3/8” apart to allow for debris to be swept below (which was cleaned daily), and to allow for cooling air to rise.

February: Paxton and Fox continue to control the labor call; it averages 1,285 a day for the month. After the roof was completed, portions were tarped to keep the sun and heat out. The interior of the South Hall was paneled in wood, also to lessen the effects of the greenhouse heat. The fencing around the perimeter of the building is removed. The boards are recycled, and become the interior flooring. The boards are spaced about 3/8” apart to allow for debris to be swept below (which was cleaned daily), and to allow for cooling air to rise.

February 10, 1851. The first day for freight move-in. (Exhibit properties had been accepted into the country, starting on November 18).

Two Months to Show Opening

March 1851: The structure is finished in March, except for exterior painting. A show floor axiom: if there are days left before show opening, there will be people that will want and use the extra time. The daily labor call in March steadily surges from 1,613 men the first week, to 2,071 the last week of the month. Crews of more than 2,000 continue working through April. The last day to accept freight was April 15, and the exterior four color painting was completed on the 19th.

March 1851: The structure is finished in March, except for exterior painting. A show floor axiom: if there are days left before show opening, there will be people that will want and use the extra time. The daily labor call in March steadily surges from 1,613 men the first week, to 2,071 the last week of the month. Crews of more than 2,000 continue working through April. The last day to accept freight was April 15, and the exterior four color painting was completed on the 19th.

Show Opening Day

Thursday May 1, 1851: Noon. The building complete, the exhibitions in place, doors open to 25,000 fans who pay the equivalent of 350 pounds to view the Exhibition on Opening Day. Crowds standing outside are estimated at 300,000. More than 6 million visitors toured the Crystal Palace in the next five and a half months.

What qualifies this building as an I&D project? And why is it considered the “Biggest I&D Project in the History of the World?”

It was an I&D project because it was designed and built as a temporary installation. After the show, it was dismantled in three months (less than half the time of the install). Then it was shipped to Sydenham Hill, London, and rebuilt in a different configuration.

It’s the biggest I&D project for several reasons: it was big in terms of size (33 million cubic feet, 990,000 square feet of exhibit space, and 978,850 square feet of glass); it was big in terms of time (it took seven months, working six days a week, to build the structure); it was the big in terms of labor (the crew started out at 30 on day one, and steadily increased to 2,000+ temporary workers—and like any good I&D job, the crews, and their size had to be managed and controlled); and most importantly, it was the biggest in terms of significance—this show was a defining moment of the Industrial Revolution, and a seminal event of the Victorian Era; the building inspired hundreds, if not thousands, of future venues. In time, other projects would be larger. And some would be temporary—but none were designed to be dismantled and re-installed in a different location, except for the Crystal Palace. And none would be as historically significant.

It’s the biggest I&D project for several reasons: it was big in terms of size (33 million cubic feet, 990,000 square feet of exhibit space, and 978,850 square feet of glass); it was big in terms of time (it took seven months, working six days a week, to build the structure); it was the big in terms of labor (the crew started out at 30 on day one, and steadily increased to 2,000+ temporary workers—and like any good I&D job, the crews, and their size had to be managed and controlled); and most importantly, it was the biggest in terms of significance—this show was a defining moment of the Industrial Revolution, and a seminal event of the Victorian Era; the building inspired hundreds, if not thousands, of future venues. In time, other projects would be larger. And some would be temporary—but none were designed to be dismantled and re-installed in a different location, except for the Crystal Palace. And none would be as historically significant.

Bob McGlincy is director, business management at Willwork Global Event Services. He can be contacted at Bob.McGlincy@willwork.com