Exhibit City News welcomes a new bi-weekly column, The Tradeshow Times by Willwork’s Bob McGlincy, who promises to alternate between tradeshows today, tomorrow and yesterday. We begin with one from yesteryear—the first modern tradeshow which opened in London in 1851.

”The more you know about the past, the better prepared you are for the future.” Theodore Roosevelt.

by Bob McGlincy, director, business management, Willwork Global Event Services

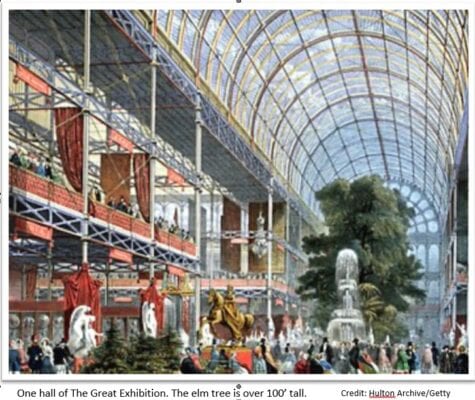

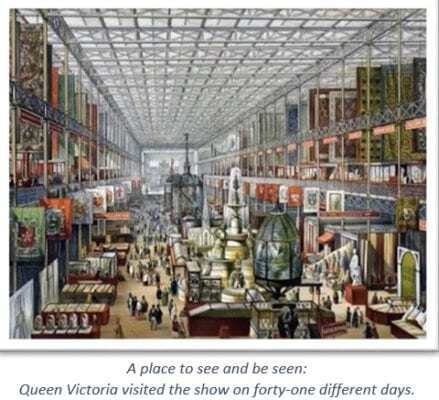

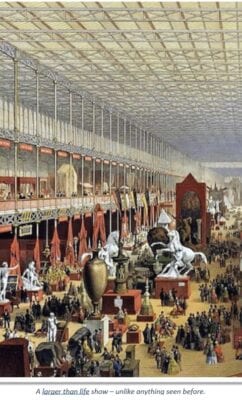

“The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations” opened in London on May 1, 1851, and closed October 15, 1851. It was a seminal event of the Victorian era, and a defining moment in tradeshow history. As a show, it was huge, international, inspiring, breath-taking, unique, enormous, and excessive—the building was four times larger than the biggest exposition hall in the world at that time; the event was global in scope and hosted industries from 44 countries; the show d

“The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations” opened in London on May 1, 1851, and closed October 15, 1851. It was a seminal event of the Victorian era, and a defining moment in tradeshow history. As a show, it was huge, international, inspiring, breath-taking, unique, enormous, and excessive—the building was four times larger than the biggest exposition hall in the world at that time; the event was global in scope and hosted industries from 44 countries; the show d isplayed more than 100,000 exhibits, and attracted more than 6 million attendees in five and a half months.

isplayed more than 100,000 exhibits, and attracted more than 6 million attendees in five and a half months.

The exhibition exceeded all expectations, and proved to be a colossal success. It was specifically designed to be a large, international event, and to showcase Great Britain as the industrial leader in iron, steel, machinery and textiles. One of the stated goals, was that technology (especially British technology) was the key to a better future. Nothing like the building or the show had ever been seen before in London, or for that matter, anywhere in the world.

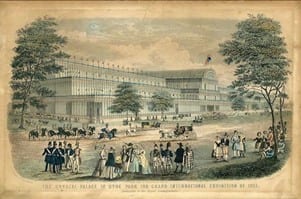

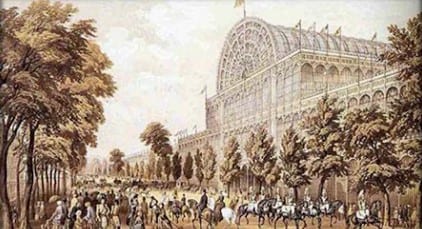

The London press, and much of Parliament, were initially opposed to the exposition and its proposed location in Hyde Park. But halfway through construction, the press titled the building “The Crystal Palace” and once the show opened, proclaimed it to be, “The Eighth Wonder of the World.”

Many words have been used to describe this show: Biggest. Best. Monumental. Historic. Trendsetting. Colossal. Transcendent. Enormous. Awe-inspiring. Maybe the most accurate description is in the name itself, “Great.” And was it ever! The Exhibition crushed the competition, and created the model for future expositions, fairs and tradeshows. Perhaps the best way to understand the magnitude and significance of this show, is to review the number of records it established, many of which still stand today:

First international exposition. It brought countries, businesses and products together from around the world. Literally. All under one roof, and at the same time.

First international exposition. It brought countries, businesses and products together from around the world. Literally. All under one roof, and at the same time.- First show to make a profit. 186,346 pounds in 1851. Equivalent to tens of millions of dollars today. Possibly the most profitable tradeshow ever. The next profitable show would be the 1889 Paris Exposition.

- First show with no government funding. Initial money was accumulated through subscriptions, donations, dinners, and other fund-raising events. Over h

alf of the money was raised was from outside London. All public funding. No private companies were involved.

alf of the money was raised was from outside London. All public funding. No private companies were involved. - First show to sell tickets and charge for admission. Included differential pricing and season ticket holders. Used turnstiles to count and record the number of visitors. Prices were lower during the week, and later in the season. Ladies tickets were less expensive.

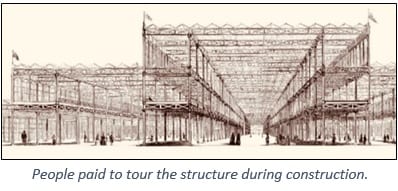

First show to charge admission to a construction site. Up to 3,000 a day paid to tour during construction. Also paid to view after completion, and before opening.

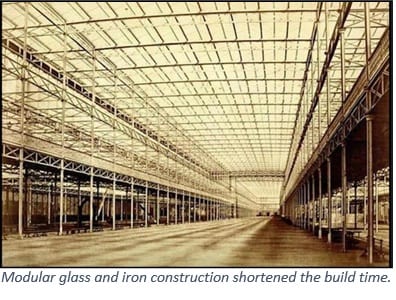

First show to charge admission to a construction site. Up to 3,000 a day paid to tour during construction. Also paid to view after completion, and before opening.- First glass and metal convention center. People paid to tour the structure during construction. Glass was not a

common construction material at this time. This building inspired hundreds of convention center designs.

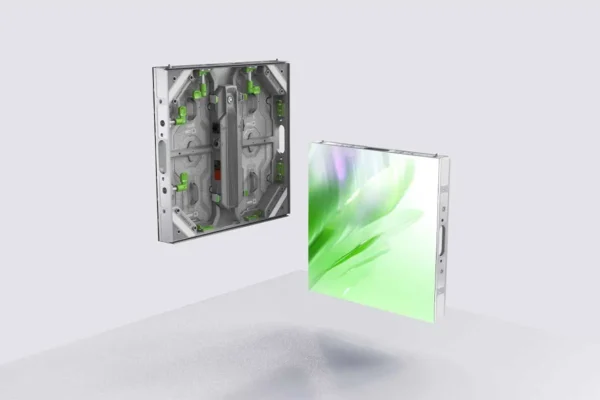

common construction material at this time. This building inspired hundreds of convention center designs. - First large scale modular construction. Pre-fabricated, and pre-tested prior to installation. Unique and necessary due to very tight time constraints.

First show to exceed 1,000,000 visitors. 6,039,722 paid attendees in five and a half months. Ten times the previous published record, and almost a third of the population of England.

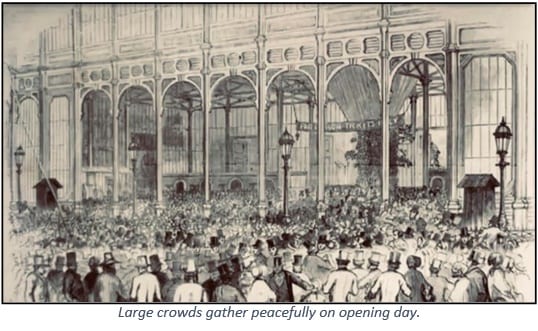

First show to exceed 1,000,000 visitors. 6,039,722 paid attendees in five and a half months. Ten times the previous published record, and almost a third of the population of England.- Largest show opening crowd

, until 1876. Day One saw 25,000 enter while more than 300,000 stood outside, watching.

, until 1876. Day One saw 25,000 enter while more than 300,000 stood outside, watching. - Largest one day attendance. 109,915 people on October 9, 1851. Held record for 25 years (until October, 9, 1876 at the Philadelphia Exposition).

- Largest Exhibit space in the world in 1851. Four times larger than any other exposition center in the world, at that time.

Largest number of exhibitors. More than 14,000 exhibitors which was more than 2.5 times the previous record.

Largest number of exhibitors. More than 14,000 exhibitors which was more than 2.5 times the previous record.- Largest number of exhibited products. More than 100,000 exhibits.

- First public flush toilets. George Jennings volunteered structures, toilets and labor. Charged a penny. Made 1,769 pounds ($198,128 today).

- First show to sell a sponsorship. 990,000 sq.ft. of exhibit space which was four times larger than any previous building.

- Largest building in the world in 1851. At 33,000,000 cubic feet and more than 1/3 mile long, it covered 19 acres.

- Largest construction project at the time. It used 10,080,000 pounds of iron, 293,655 panes of glass and 30 miles of gutters.

- Schweppes paid for a beverage and food sponsorship. Made 45,000 pounds ($5 Mil today). Three refreshment centers sold a total of 1,927,337 beverages. Established a brand.

Most number of countries exhibiting. Businesses from 44 countries traveled to England, many at the expense of their governments. Previous record, 1. New record, 44. This number would not be equaled or exceeded for the next 42 years (not until Chicago hosted 46 countries in 1893).

Most number of countries exhibiting. Businesses from 44 countries traveled to England, many at the expense of their governments. Previous record, 1. New record, 44. This number would not be equaled or exceeded for the next 42 years (not until Chicago hosted 46 countries in 1893).- First World’s Exposition. More than 100 in over 20 countries since 1851. Called World’s Fairs in the U.S.

- First modern tradeshow. Perhaps the most important designation of all, it laid the foundation, and unfurled the blueprint for shows to follow for next 170 years.

How huge was this show?

“I was there for five days, and still did not see it all,” said Horace Greeley, founder and editor, New York Tribune. To put it into perspective, compare it to centers and shows in the U.S. in 2019. The Crystal Palace, if it still existed, would be one of the ten largest exhibit halls in the US, although Chicago, Las Vegas and Orlando do have show floors more than double its size. The ceiling of the Crystal Palace was twice the height of the highest ceiling at McCormick Place. No show would have more exhibitors—not even close—and very few would have the same or larger footprint (CES, SEMA, and Pack Expo are three that are larger). And when it comes to attendance, there is no comparison. Only two B2B shows (Music Merchants and SEMA) had more total attendance than the highest one day attendance at this event, and even huge consumer shows rarely draw more than a million people for the entire show.

Another way to picture the size of this show: All the conventions in Las Vegas in 2019, combined, attracted a record setting 6.6 million visitors to the city. In 12 months and thousands of meetings, Las Vegas attracted only ten percent more than London did in one show in five and a half months, 168 years earlier.

Another way to picture the size of this show: All the conventions in Las Vegas in 2019, combined, attracted a record setting 6.6 million visitors to the city. In 12 months and thousands of meetings, Las Vegas attracted only ten percent more than London did in one show in five and a half months, 168 years earlier.

Admittedly, it is not an apples to apples comparison. The Great Exhibition became a cultural phenomenon; it was a must-see event; it was the first world’s fair. But again, to keep it in perspective: the event drew more than 6 million people at a time when the population of greater London was 2,650,000, and the population of all of England was less than 18 million.

So how did this happen? What were the origins of the show? Who were the principals players involved? How did it all come together?

It takes a team to create any type of success. And that is definitely true here: show site construction required nearly 2,000 workers, six days a week, every week for more than half a year. There was the Royal Society, there was the Building Committee, and there were all the

contractors involved … the list could go on.

The three heroes of this story have to be the Queen, the Prince, and the gardener. Certainly Henry Cole and Charles Fox played instrumental roles, but lacking any one of these first three, it is unlikely that the Exhibition would have happened.

Queen Victoria rarely receives credit for the Exhibition. But without her involvement, it is doubtful the show would have happened. Certainly, without her determination, it would not have been as successful. Queen Victoria proved instrumental in bringing the Exhibition to reality in several ways: 1) she appointed Albert to chair the Commission that created the Exhibition;

2) the building was constructed in Hyde Park, which was royal land and needed her permission and approval; 3) her support was beneficial in priming the subscription funding; and 4) she insisted—against much political pressure and advice—on being present and opening the Exhibition on Day One. There was a valid reason to suggest the Queen should fear going out in public, in the midst of such a large crowd: There had been six assassination attempts on her life between June 10, 1840 and June 27, 1850. Her announced presence at the show dramatically increased support for and attendance at the show. The last reason, maybe the most compelling reason of all, had she not married Albert, he would not have been there to proclaim the advantages of an international exhibition.

Victoria ascended the throne June 20, 1837, at the age of 18. She proposed to Albert in October of 1839, and they were married on February, 10 1840. Albert was not a favorite of the press or Parliament, as many felt the Queen had married a lesser royal. Theirs was an arranged marriage, but she had several options, and she chose Albert. It appears to have been a happy marriage, as they had nine children (and surprisingly for the period, all the children survived to adulthood).

Upon Albert’s death in 1861, Victoria went into mourning, and stayed dressed in black for the next 40 years, until her death in 1901.

Prince Albert (pictured right) is the visionary and the driving force behind The Great Exhibition. He wanted an international show, one focusing on the benefits of technology, and he wanted it to be the biggest and best show in the world—one befitting, and benefiting, Britain’s image and stature. He sought to “build a cathedral to free trade” and “invite every country to send its creations.” Although his ideas were not initially popular, he was persistent in stating them. He would not be deterred by criticism from Parliament, or from the press.

Prince Albert (pictured right) is the visionary and the driving force behind The Great Exhibition. He wanted an international show, one focusing on the benefits of technology, and he wanted it to be the biggest and best show in the world—one befitting, and benefiting, Britain’s image and stature. He sought to “build a cathedral to free trade” and “invite every country to send its creations.” Although his ideas were not initially popular, he was persistent in stating them. He would not be deterred by criticism from Parliament, or from the press.

In 1843, Albert was elected president of the Society of the Arts. In 1846, Henry Cole, editor of the Journal of Design, joined the Society shortly before the Royal Charter changed the name to the “Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts,  Manufacturers and Commerce.” Both men were familiar with the 1844 Paris Exposition, and wanted to do something similar in England. They developed three expositions in 1847, 1848, and 1849; they were not major shows, but attendance increased each year from 10,000 to 73,000 to 100,000 in 1849.

Manufacturers and Commerce.” Both men were familiar with the 1844 Paris Exposition, and wanted to do something similar in England. They developed three expositions in 1847, 1848, and 1849; they were not major shows, but attendance increased each year from 10,000 to 73,000 to 100,000 in 1849.

These shows did not attract governmental interest or support for a proposed larger event. However, once it was determined that the show would be self-financing, Parliament was less antagonistic.

Still there were obstacles: the xenophobic press, and many members of parliament feared an event like the Exhibition would be an invitation to revolution, and that bringing foreigners onto the soil could lead to more disease. This fear was not totally unwarranted: the revolutions of 1848 across western and central Europe and the Chartist Movement in England were recent memories; second there had been a cholera epidemic in London in 1848 and 52,000 people perished from the disease (the epidemic in Russia killed more than a million people between 1847 and 1851). Another obstacle, many people did not want a large structure built in Hyde Park, destroying the ground’s pristine beauty. Lastly, there was the problem of what to build, and how to build it—the building had to be temporary and inexpensive; but it also had to be huge, impressive and able to be constructed within a limited time frame.

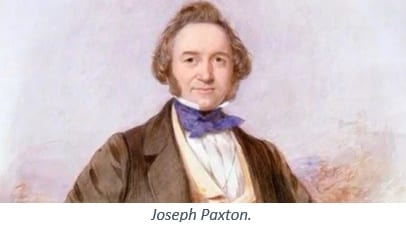

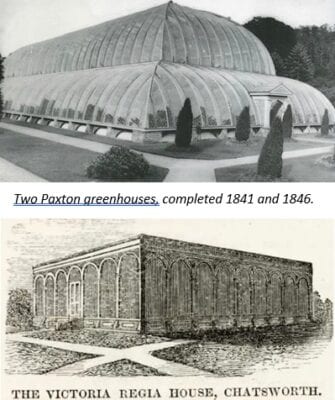

Joseph Paxton would solve the “build” problems. He was the designer and builder of the Crystal Palace. Although the press referred to him as “a gardener,” he was a landscape designer, architect and builder. At the age of 20, he became head gardener for the Duke of Devonshire. His public garden designs and work at Birkenhead Park directly influenced the design of Central Park in New York City. But more importantly for this story, he was a pioneer in working with glass and metal. Between 1833 and 1848, he designed and built three large greenhouses for the Duke.

Joseph Paxton would solve the “build” problems. He was the designer and builder of the Crystal Palace. Although the press referred to him as “a gardener,” he was a landscape designer, architect and builder. At the age of 20, he became head gardener for the Duke of Devonshire. His public garden designs and work at Birkenhead Park directly influenced the design of Central Park in New York City. But more importantly for this story, he was a pioneer in working with glass and metal. Between 1833 and 1848, he designed and built three large greenhouses for the Duke.

The Great Conservatory at Chatsworth, finished in 1841, was 227 feet long by 123 feet wide by 61 feet high. At the time, it was the largest glass building in the world. In 1846, Paxton completed construction of the Chatsworth Lily house. He knew where to find craftspeople and contractors —specifically ironworkers and glaziers—and he would use these contacts in the construction of the Crystal Palace. Paxton knew Robert Chance; Chance was a British pioneer in glassmaking technology, and a partner in Chance Brothers, the leading glass manufacturer in England. Paxton influenced Chance to produce glass in four foot lengths (the previous lengths were a maximum three feet long). Paxton also worked with Charles Fox, of Fox and Henderson.

The Great Conservatory at Chatsworth, finished in 1841, was 227 feet long by 123 feet wide by 61 feet high. At the time, it was the largest glass building in the world. In 1846, Paxton completed construction of the Chatsworth Lily house. He knew where to find craftspeople and contractors —specifically ironworkers and glaziers—and he would use these contacts in the construction of the Crystal Palace. Paxton knew Robert Chance; Chance was a British pioneer in glassmaking technology, and a partner in Chance Brothers, the leading glass manufacturer in England. Paxton influenced Chance to produce glass in four foot lengths (the previous lengths were a maximum three feet long). Paxton also worked with Charles Fox, of Fox and Henderson.

They were a railway equipment company specializing in structural iron for railway bridges, stations, and roofs. Chance Brothers, and Fox and Henderson, would prove to be essential contractors.

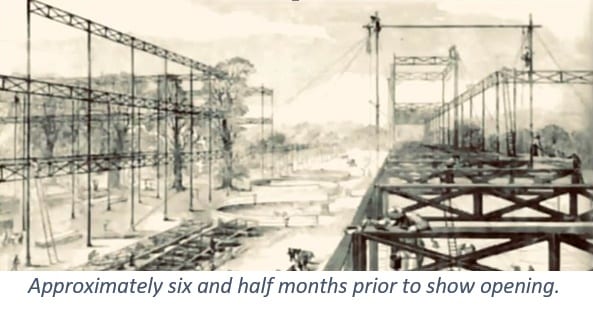

The design of the Crystal Palace projected a unique spatial look, one befitting the technological advances that the Exhibition showcased. The blueprint was a daring plan, and one that Paxton executed brilliantly. Once construction started, he proved to be a masterful I&D magician

who managed to bring the project in ahead of schedule. Despite the building’s mammoth size, it was actually an I&D project. Why? For three reasons: 1) the Crystal Palace was designed as a temporary structure (after the show it was dismantled, moved to Sydenham Hill, London, and installed again); 2) it was a massive labor job, involving thousands of temporary workers, for seven months; and 3) it had unbelievably tight time constraints with an unforgiving deadline. Not all future expositons would open on time; but this one did.

Paxton’s input was critical because one year prior to show opening, the Great Exhibition was still only an idea—there was no land, no design and no approval. In fact, even ten months before the show opening date, there was still no consensus on a design, let alone an approved bid. How it all came together is fairly unbelievable. Preliminary work would start July 30, 1850. But before that could happen a lot of problems had to be overcome. Getting other countries to buy into the idea of an international exposition wasn’t a problem. Getting Britain to do so, was.

Paxton’s input was critical because one year prior to show opening, the Great Exhibition was still only an idea—there was no land, no design and no approval. In fact, even ten months before the show opening date, there was still no consensus on a design, let alone an approved bid. How it all came together is fairly unbelievable. Preliminary work would start July 30, 1850. But before that could happen a lot of problems had to be overcome. Getting other countries to buy into the idea of an international exposition wasn’t a problem. Getting Britain to do so, was.

But resistance in Parliament, and in the British press, wasn’t nearly as challenging as finding a way to build a structure in time. My next column, “The Biggest I&D Project in History” will detail that remarkable project.

The Great Exhibition was a spectacular show of historic proportion. It helped shape and define Britain’s position in the world; and it demonstrated the superiority of British technology. It would draw the blueprint for success for future shows.

Bob McGlincy is director, business management at Willwork Global Event Services, Inc., based in Massachusetts. Willwork creates engaging, energized and exceptional event experiences. Contact him at Bob.McGlincy@willwork.com.