The 1939 New York World’s Fair

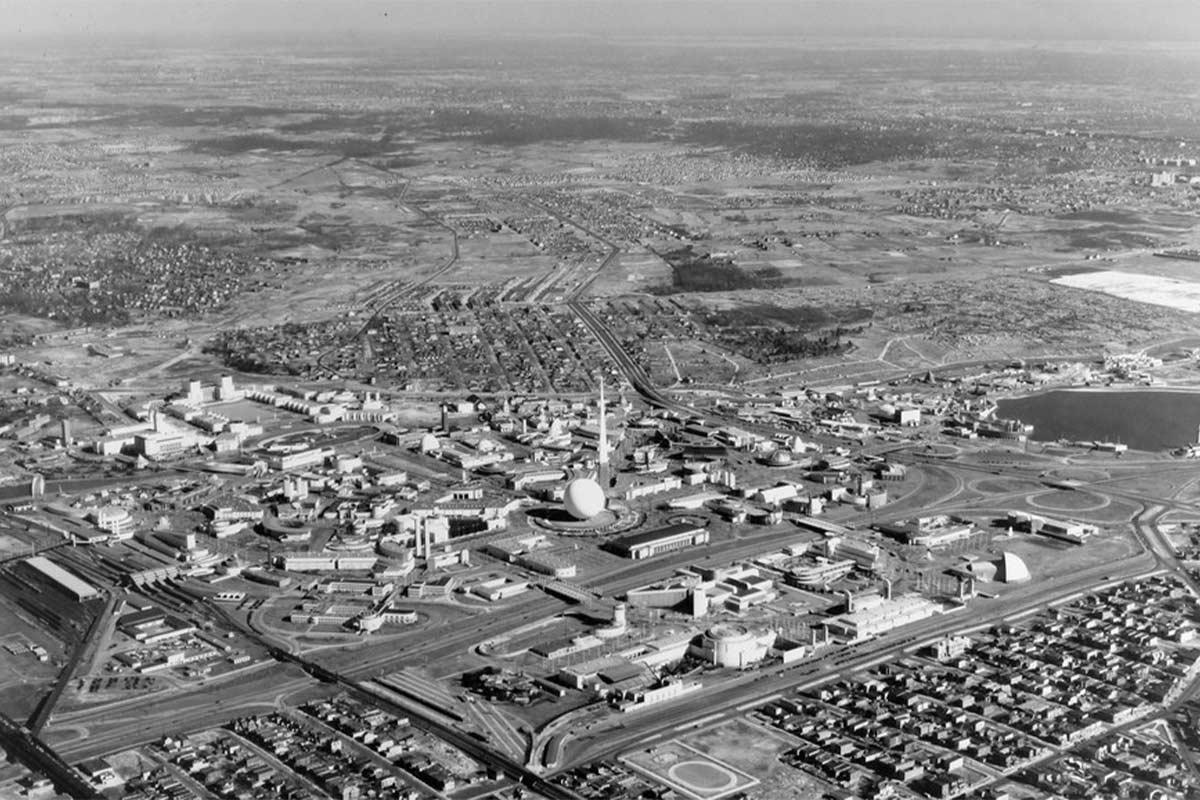

The 1939 New York World’s Fair opened on April 30, the 150th anniversary of George Washington’s New York City inauguration. The Fairgrounds were huge, hosting 62 countries, 35 US states, 1,500 businesses, and covering 1,200 acres—an area approximately the size of 200 city blocks.

What would it be like to go back in time, and walk through the Fair?

Entering the Fair

Visitors entered the Fairgrounds off Corona Avenue, passing between either the north or south gate. The back of the Chrysler Building bordered the street, the Railroad Building was to the far left, and the Aviation Building to the far right. Once inside, past the Chrysler Building, were the massive pavilions for Goodrich, General Motors, Ford and Firestone.

The Fairgrounds were laid out in seven geographical color-coded zones, each representing different areas of interest. Liberty Lake and the Amusement Zone were in the distance at the far back right. Rising majestically in the center, visible from midtown Manhattan, were the two landmarks of the Fair: a three-sided, 610-foot-tall tower; and a 200-foot wide, 18-story sphere.

The Trylon and the Perisphere

Crowds gravitated towards these icons as if pulled by a tractor beam. After entering the Trylon, the group herded up the world’s tallest escalator, then funneled into the Perisphere. The interior was twice the size of Radio City Music Hall and showcased an imagined glimpse into the year 2039.

Spectators stood on a rotating platform, above a diorama displaying “the utopian landscape of the future.” The “ride” took six minutes. Then the awe-stuck guests descended the Helicline: an 18-foot wide, 950-foot long ramp that circled the Perisphere and offered a panoramic view of the Fairgrounds and the New York skyline.

Back on the ground, there were so many things to see and do that it was almost a sensory overload. There were parades, flags, lights, colored fountains, music, sculptures, people, murals, stunning architecture, and souvenirs. There were 200 foreign, domestic, and corporate pavilions, and over 300 places to eat. The Amusement Zone was larger than the entire Paris Expo of 1937, and housed 50 major concessions, including some after-dark, adult entertainment.

Engaging Audiences

The Fair promoted technology and business as the pathway to a better tomorrow.

The 100 corporate pavilions ranged in size from 10,000 square feet (the House of Jewels) to 300,000 square feet (General Motors). Many corporations had their own separate stand-alone structures; others joined together exhibiting similar products inside one building. Crowds enjoyed seeing new products and watching live demonstrations.

Innovations and Displays

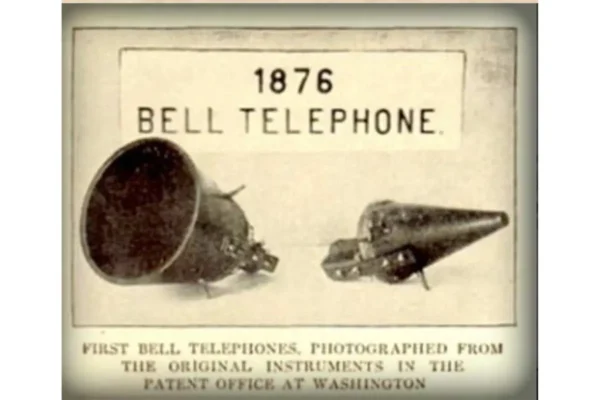

AT&T introduced the first electronic voice synthesizer, VODER, which mimicked human sounds. They offered hourly lottery winners free long-distance calls anywhere in the country.

Borden presented “The Dairy World of Tomorrow.” A 50-foot-high glass rotunda enclosed a revolving platform, where a herd of 150 pedigreed cows were mechanically washed, dried, and milked.” Elsie the Cow proved to be the star of the show, and a hit with children at the Fair.

Carrier constructed a 70-foot-tall replica of an igloo, with two 40-foot-tall thermometers—one displaying the temperature outside, and the other the temperature inside (which some days was 20 degrees cooler). Air conditioning had been installed in some commercial buildings but was unknown to most of the public. An added bonus inside was an Aurora Borealis simulation displayed on the ceiling. In 1940, a dozen other pavilions provided the cooling comfort of air conditioning.

Chrysler offered a simulated rocket ride to London. They produced the first public animated 3D film, “In Tune with Tomorrow;” it demoed the assembly process of how cars were built. They presented a “talking car,” showed a movie about the history of transportation, and displayed four new car brands. Outside the building was their “frozen forest”—a space where people could pause, sit, relax and cool down on a hot summer day.

Consolidated Edison attracted visitors with an exterior 3,000 square foot waterfall. Inside, a detailed diorama of New York City showed how ConEd electrified the five boroughs, with a full day passing from day to night in 12 minutes.

DuPont debuted a revolutionary man-made fiber at the Fair, a silk-replacing synthetic named Nylon. A year later when nylon stockings went on sale in a nationwide rollout, DuPont sold four million pairs in the first four days. Other products displayed in the “Better Living Through Chemistry” exhibit included Lucite, antifreeze, Freon, plastic, and nylon sutures, fishing lines, and toothbrushes.

Ford demonstrated how machine-made products could reduce costs and create new jobs. They offered chauffeured rides in the newest models, with cars quickly accelerating up a spiral ramp for a dramatic view of the Fair. Their “Cycle of Production” was a 100-foot wide revolving turntable parading all phases of work, starting with raw materials. The building and gardens covered seven acres and displayed decades of Ford cars and trucks.

Firestone housed a full-scale model farm, a diorama of a rubber plantation, and a mock-up of a tire factory, where visitors could watch a tire being made from raw material to completion. Visitors could order tires onsite. Outside the pavilion stood the world’s largest tire.

General Electric (GE) attracted attention with an ear-splitting, 10-million volt, lightning flash. Inside their House of Magic, the company X-rayed a swathed Egyptian mummy, demoed products, and in 1940, showcased their own television set. GE used booth staffers to conduct market research, a novel concept at the time.

General Motors created the first fully immersive experiential exhibit. It cost over $7 million (equivalent to $160 million today) and entertained more people than any other attraction at the Fair. “Futurama” presented a glimpse into 1960 with skyscrapers, heliports, multi-lane interstate highways, cloverleafs, and country roads. Comprised of 408 dioramas on one acre, the set included 500,000 buildings, one million trees, 40,000 stationary vehicles and another 10,000 vehicles in motion. Spectators, seated in moving chairs with a self-contained sound system, enjoyed an 18 minute “flight” over the landscape.

IBM exhibited inside the Business Systems and Insurance Pavilion. They displayed electric typewriters and calculators, time clocks, printers, card punchers and sorters. Additionally, they showcased modern paintings from 79 countries.

Kodak introduced color film at the Fair. Large photos projected on exterior walls attracted crowds, (one photo captured a baseball shattering a pane of glass). Inside the “Hall of Light,” color photos lit a huge 187×22-foot wall. Guests could view exhibits, murals, equipment, or even relax in one of two movie theaters. Back outside, couples and families posed beside a miniature Trylon and Perisphere—a true Kodak moment, and the most photographed image of the Fair.

RCA transmitted the first live commercial television broadcast on opening day and replayed it inside their pavilion. They showcased thirteen televisions; each set had a 12” screen, reverse projected onto a larger 3×4-foot space. They filmed attendees walking around the fair and produced two hour-long programs each week. The televisions of 1939 projected 441 lines of definition.

Westinghouse proclaimed modern science would make life easier through better appliances. In addition to displaying their product, the company buried a time capsule, presented the first computer game, and introduced Elektro, a seven-foot tall metal robot: he walked, he talked, he smoked, he answered questions. In 1940, Elektro was joined on the stage by Sparko, his robot dog.

US Steel presented a dome shaped pavilion, supported by exposed steel beams. Inside the 26,000 square-foot structure, dioramas, murals, and live demos engaged crowds.

These 15 showstoppers were only part of the Fair—there were another 182 buildings housing exhibits, plus a steroid-infused Midway. There was a lot to see.

But the Fair did not exist in isolation. War broke out in Europe in September, and several countries did not return in 1940. On July 4 that year, a bomb in the British Pavilion killed two NYC police officers trying to defuse it.

A Final Accounting

Nearly 45 million paying customers passed through the Corona Gates those two summers. Unfortunately, expenses were greater than revenue, and the Fair lost $18.7 million. Fingers pointed in many different directions, but the loss was mainly due to mismanagement, wretched excess, and a lack of successful cost controls. Six years earlier the Chicago World’s Fair made a profit.

On a positive note, the 1939/1940 World’s Fair created tens of thousands of jobs and had an economic impact of $280 million for New York City. It contributed 80 million pounds of salvageable steel for the war effort. It transformed a dump into the future home of the New York Mets’ Shea Stadium and the U.S. Open. It showcased new inventions, developed business sales and promoted brand recognition.

It fashioned memories that would never be forgotten.

This story originally appeared in the Q2 2025 issue of Exhibit City News, p. 22. For original layout, visit https://issuu.com/exhibitcitynews/docs/exhibit_city_news_-_apr_may_jun_2025/22.