What do you think of when you hear the name, Thomas Edison? Does a light bulb go off in your head?

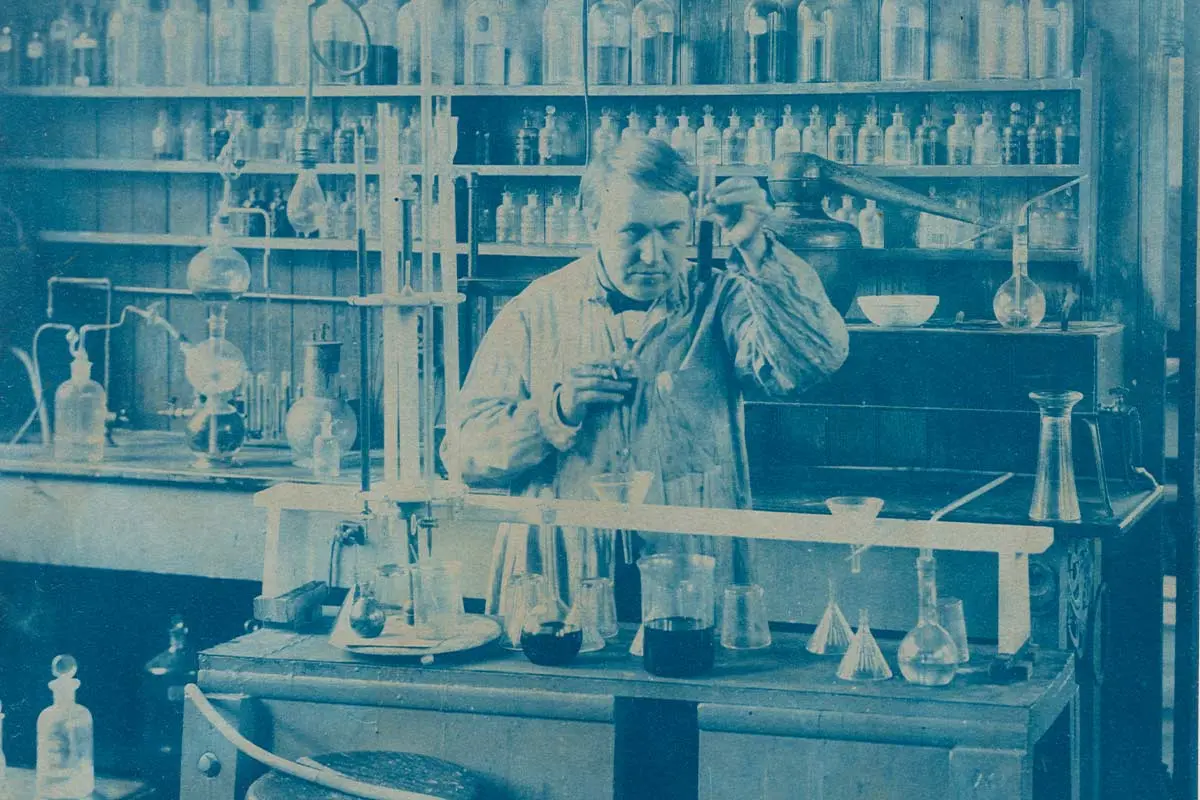

A visionary, a businessman, a self-promoter, Edison averaged one invention every 11 days for 40 years. He filed more than 1,000 patents. His products ranged from the automatic telegraph and the telephone transmitter to the phonograph, light bulbs, electric distribution systems, motion picture cameras, and alkaline storage batteries. Edison is the reason the United States uses its standard voltage system in homes today. What many people don’t realize is that he was a marketing maven. More so than any other individual or business in the 19th century, Edison exhibited at expositions. He did so to fund his passion for inventing.

Edison believed in applying science to make the world a better place. He sought to improve ideas (both his and others) to create practical products that benefited the public. He coined the words phonograph, filament, talkies, films, and popularized the word, light bulb. Edison created an invention factory in Menlo Park, laying the foundation for future R&D labs at AT&T, DuPont and Xerox. Edison was a self-made success story, but his success didn’t happen overnight.

There was a time when Edison was unknown. He realized he needed to make people aware of his inventions and their value. He first sold a few patents. Then he began exhibiting at industrial expositions and World’s Fairs. He won awards and medals. As his reputation increased, so did the demand for his products.

Exhibiting at Expositions and Fairs.

Brilliant ideas and remarkable products are meaningless if no one knows about them.

The American Institute Fair. Founded in 1829, this New York City event offered manufacturers and inventors a chance for recognition and financial prizes. In 1870, Edison garnered a first-place award for his glass-domed, universal stock printer. It was his first-time exhibiting; it would not be his last.

The Centennial Exposition. Philadelphia welcomed the World’s Fair to America in 1876. Edison initially planned on exhibiting in a 400 square foot booth space, but he wanted better exposure, so he moved into the Western Union exhibit. Edison showcased his automatic telegraph (capable of recording 1,000 words a minute), his quadruplex telegraph system (which transmitted four separate messages simultaneously over one wire). He displayed his electric pen (a duplicating system similar to a mimeograph) and a range of printers.

Walking the show floor inspired Edison. The Wallace-Farmer dynamo powered a system of arc lights and triggered his work on incandescent illumination. After viewing Bell’s new telephone, Edison thought he could make it more functional. His invention of the phonograph grew out of his work developing a telephone transmitter.

The 1878 Paris Exposition. Intended to aid the hard-of-hearing, Edison’s megaphone magnified sound up to 50 times. Another display demonstrated his phonograph. It was the first device that could record and play back sound; it was so original that many in the audience suspected a ventriloquist to be hiding somewhere nearby. Perhaps even more important, and life-altering, were Edison’s inventions of the carbon microphone and the chalk receiver, which dramatically improved the performance and functionality of Bell’s telephone.

After Paris, Edison entered one of the most prolific phases of his illustrious career. In one 4-year period, Edison averaged filing one patent every 4.5 days. In 1879 he demonstrated a bulb that glowed continuously for a 14.5 hours. However, before electricity could light up the night, its existence had to be demonstrated to the public. Electrical shows became the first industry-specific tradeshows.

For Edison to exhibit in Europe required a significant commitment. Today a trip from New York to Paris is a seven to eight hour flight. In the 1880’s it took ten to fourteen days—first by steam ship and then by rail.

The International Exposition of Electricity. In 1881, Paris hosted the first event devoted to the science and technology of electricity. Edison displayed multiple products: a vote recorder; a two, four, and eight way telegraph; the electric pen; the phonograph; transmitters; dynamos; and electric lights. Against stiff competition, Edison’s high resistance lamp design was declared “most efficient” and awarded “Best of Show.” An additional five other Edison products won gold medals.

The 1882 Crystal Palace Electrical Exhibition. Edison again demoed multiple products, this time in London. After his successes in Paris, he was hailed as a conquering hero, and had his name spelled overhead in lights. That same year, he developed an electrical distribution system in New York City.

The International Electrical Exhibition of 1884. Philadelphia’s Franklin Institute hosted 196 companies and 280,000 visitors over five weeks. Several of Edison’s companies displayed lights, dynamos, and power distribution systems for lighting houses, hotels, and hospitals. Edison’s attention-attracting exhibits included a lit floor, a pyramid with 2,600 flickering lights, and a 30-foot fountain ablaze with color.

Other shows occurring this decade included electrical expositions in Munich, Vienna, plus two more in London. Edison’s companies exhibited in these shows, as well as ones in Louisville and New Orleans.

The 1889 Paris Exposition. Edison leased an acre of exhibit space to showcase his inventions. The booth space was slightly larger than 100 x 400-feet. The booth displayed 493 separate inventions. The centerpiece of the exhibit was a 40-foot-high bulb-like structure, consisting of 20,000 individual incandescent light bulbs. He demonstrated his phonograph in a separate listening room and attracted thousands of people daily. Edison was there for five weeks and was awarded France’s coveted Legion of Honor.

The 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. Edison and JP Morgan founded a new company called General Electric (GE) a year before the show. They spent the equivalent of $16.4 million to exhibit there. GE won an astonishing 32 gold medals. Edison’s Tower of Lights dazzled with 18,000 light bulbs attracted eyeballs, but his kinetoscope, a prototype motion picture camera, went on to revolutionize the entertainment industry.

After Chicago, Edison’s companies exhibited in expositions in San Francisco, Atlanta, Nashville, and Omaha, as well as in the 1896 National Electrical Exhibition in New York City. At that show, Edison displayed household appliances, a fluoroscope, and lighting fixtures.

The National Electric Light Association was a trade association for electrical enthusiasts. Their first show was in Chicago in 1885. It then rotated to New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and St. Louis. Edison, Tesla, and Westinghouse were honorary members and frequent exhibitors. At the 1899 NELA show in New York City, Edison featured his alkaline storage battery. The talk of that show was an Edison movie titled, “The Kiss.” It was an eighteen second reenactment of the final scene from a popular stage musical. Only the kiss was on film, and displayed in public to a large crowd. Scandalous!

The 1900 Paris World’s Fair. GE exhibited multiple products and was said to be the second most popular attraction at the Fair. The Eiffel Tower was the first. Edison displayed his x-ray machine and a rubber conveyor belt which won a grand prize. He showcased his movie projector, the Kinetoscope, and filmed short movies of the Fair, the crowds, and the Champs-Elysee.

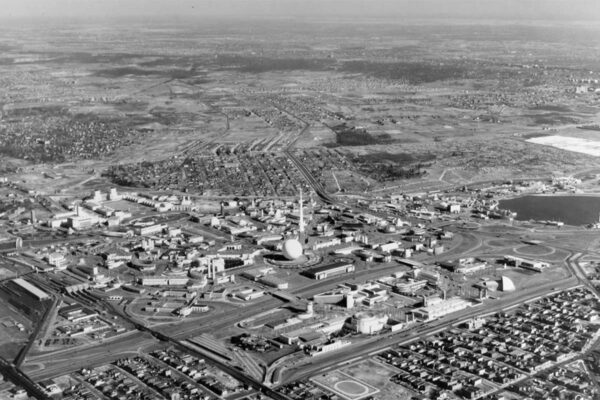

The 1901 Pan American Exposition. Buffalo wanted to outshine Paris. Cheap electricity from the Niagara Falls power plant, coupled with Edison’s 2 million light bulbs, created an electrical marvel. Edison filmed a series of both nighttime and daytime scenes.

The St. Louis World’s Fair. Edison built the power plant for the 1904 Fair and was asked to oversee all presentations in the Palace of Electricity. One of his crowd-fascinating displays was a working factory demonstrating the production of incandescent light bulbs. The Fair itself was an electrical marvel. At night, the buildings blazed with light and created a spectacular panorama that outshined the previous fairs in Buffalo and Chicago.

Throughout the remainder of the decade, Edison and his companies exhibited in cities across America, including Charleston, Portland, Jamestown, and Seattle.

The National Association of Talking Machine Jobbers. At this 1911 show, Edison introduced a prototype disc player which replaced cartridges on his phonograph. The sound quality was not as good, but it enabled longer recordings. Edison also showcased an apparatus to add color and sound to movies.

1915 Pan-Pacific Expo. In addition to existing products, including his new record player, Edison displayed a submarine alkaline storage battery. To honor his lifetime of achievements, San Francisco declared October 21 “Edison Day.”

A final observation. Edison’s passion was inventing. To finance his passion, he had to sell products. At times he teetered on bankruptcy. He occasionally delayed paying vendors and even missed some mortgage payments, but he never missed a payroll, even though he employed thousands of workers. At the time of his death, Edison was worth approximately 252 million in today’s dollars. Tradeshows work.

This story originally appeared in the Q3 2025 issue of Exhibit City News, p. 82. For original layout, visit https://issuu.com/exhibitcitynews/docs/exhibit_city_news_-_jul_aug_sept_2025/82.