At the time of his death in 1919, Henry John Heinz was worth the equivalent of $1.45 billion. His Pittsburgh factory employed 4,600 people and produced millions of bottles of ketchup a year. Decades prior, Heinz was arrested for fraud, and he had filed for bankruptcy. The charges were dropped (and in time he would repay all his creditors), but Heinz had lost everything: his business, his reputation, and even his parent’s home. His road to riches is a fascinating story, with detours and multiple stops at tradeshows.

In the 1870s, the state of food in cities was deplorable. There was no refrigeration. Food was often stored in vermin-infested containers causing meat and produce to become tainted and rancid. Sauces, often filled with sawdust as a thickener, were used to mask tastes. Heinz believed he could do better.

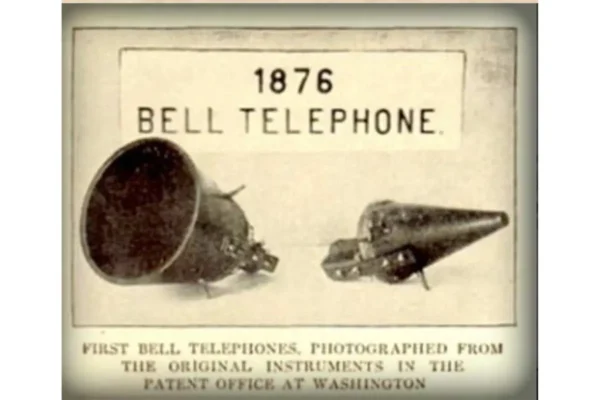

In 1876 he developed a new condiment: a tomato-based sauce with salt, onion, garlic, distilled vinegar, and brown sugar. It was sweet, sour, and slightly acidic. He packaged it in clear-glass bottles so people could see its purity (a radical idea at the time). He named it “ketchup” to differentiate his product from the existing “catsup.” His condiment was better tasting and purer than anything on the market — but he had to get people to notice it. He decided to go to the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia.

Heinz believed he could mass-produce food products and sell them nationally. He started in Pennsylvania with pickles, horse radish sauce, and ketchup — and had developed over sixty additional products by 1893.

Exhibiting in Chicago, Paris, St. Louis, and San Francisco

At the Chicago World’s Fair, Heinz was the largest commercial food distributor at the show. His exhibit, unfortunately, was located on the second level of the Agricultural Building, limiting the number of visitors.

Heinz’s solution for attracting more people to his booth was simple: he would offer free gifts to anyone climbing the stairs and stopping by the exhibit. Today, we would say his solution was obvious; but in 1893, the idea was original. Heinz hired young teens to distribute cards that could be exchanged in his exhibit for a free souvenir from the Fair. In another brilliant marketing move, he tied his gift to his product. The giveaways were small, green, pickle charms, embossed with the Heinz logo, and could be attached to bracelets or keychains. Over the summer, Heinz gave away over one million items! The campaign was so successful, attracting so many people, that there was structural damage to the building. According to an article in the New York Times that fall, “the galley floor of the Agricultural Building has sagged where the pickle display of the HJ Heinz Company stood.”

Prior to 1893, Heinz was a national business. When the Columbian Exposition launched the company internationally, Heinz exhibited at the next major international exposition.

The company won two gold medals at the Paris Exposition of 1900: the first for product quality and the second for exemplary factory conditions. Heinz accepted the awards in person. The following year, Heinz exhibited at the 1901 Pan-American Exposition, with an even larger booth space and display. He went on to exhibit in St. Louis in 1904, with a central display in the Palace of Agriculture, plus ten smaller exhibits around the fairgrounds offering regional tastings. He proceeded to exhibit at smaller shows throughout the decade. At the 1915 Exposition in San Francisco, Heinz added a movie theater adjacent to his main exhibition building.

Heinz was an innovator. He was the first to power an industrial plant with electricity. He did it before Andrew Carnegie, before JP Morgan, and even before Edison or Westinghouse. Heinz also developed a continuous flow system in his factory, utilizing an assembly line to enable workers to perform one simple task, over and over again. Heinz’s assembly line predated those of Ransom Olds and Henry Ford. Heinz’s factories were so clean, sanitary, and well-lit that he offered public tours where over 20,000 people walked his factory floor annually.

In February 2013, not quite one hundred years after the founder’s death, Berkshire Hathaway and 3G Capital purchased Heinz for $23 billion. Two years later, the company merged with Kraft Foods. Today, that company sells over 650 million bottles of ketchup annually, plus an additional eleven billion squeezable ketchup packets. Tradeshows work.

Willwork creates labor and technology solutions for experiential marketing applications, including tradeshow exhibits, corporate events, brand activations, and themed retail environments. Bob McGlincy is director, business management. He can be reached at Bob.McGlincy@willwork.com

This story originally appeared in the Q3 2024 issue of Exhibit City News, p. 18. For original layout, visit https://issuu.com/exhibitcitynews/docs/ecn_q3_2024/18.