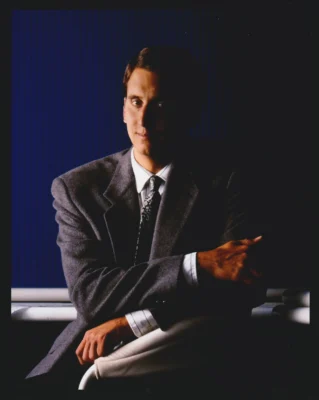

(Above: Holly Cook Macarro, political consultant in Washington, D.C., and Reid Malinovich, chairman of Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians, discuss the state of tribal gaming on Indigenous Peoples Day at Global Gaming Expo.)

By Ray Smith, Exhibit City News

As chairman of the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians, Reid Malinovich was reluctant to mention Christopher Columbus in Monday’s opening keynote for Global Gaming Expo 2022, which runs through Oct. 13 at The Venetian hotel in Las Vegas.

He said he wonders how the US government established a federal holiday for someone who discovered land where Indigenous people had lived for centuries, had worked the land and had ruled with their own system of democracy.

“It’s a time of celebration of who we are as a people, to celebrate our achievements,” Malinovich says at G2E, which honored Indigenous Peoples Day with a panel discussion on tribal gaming. “We still have a lot of work to do. Today is important to never lose sight of where we came from.”

Much of the improvement in Native Americans’ quality of life can be attributed to the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act of 1988. It paved the way for tribal casinos across America that more than tripled revenue from $11 billion in 2000 to $39 billion in 2021.

The discussion was moderated by Ernest Stevens, chairman of the National Indian Gaming Association. He pitched it as an opportunity to tell the story of his people, how they were accepted by European nations, how Indians comprise the highest per capita population to serve in the military.

“It’s hard to talk about the loss of land and genocide,” Stevens admits. “We fought our way back. Today we heal. We don’t forget, but we move forward.”

Ben Nighthorse Campbell, former US senator from Colorado and elder statesman of the panel, spoke about being assigned to Nellis AFB following his service in the Korean War, when Las Vegas was “cowboys, showgirls, veterans and gangsters, and everybody knew where they belonged.”

Campbell never thought tribal gaming would evolve into a billion-dollar industry when the gaming act was passed in 1988.

“That’s not to say it’s helped every state, because it hasn’t. A couple places it doesn’t apply. In Utah, where there’s no gambling. If you’re in a resort area, Palm Springs, you’re doing well,” he continues. “Go to North Dakota, it’s just nickels in the machines and nobody’ll drive very far to put nickels in a machine. Montana allowed slot machines in every gas station.”

Indian gaming has lifted reservations that struggled with 50 percent unemployment and 30 percent high school drop-out rates, says Holly Cook Macarro, a political consultant in Washington, DC, and member of the Red Lake Band of Ojibwe Indians in Minnesota.

Macarro was shorthanded in fighting political powers when she went to Washington in 1997. Native Americans were gravely underrepresented on Capitol Hill. The situation has improved, but not much.

“This renaissance we’re seeing right now … just the recognition of how far we’ve come, but also how far we have to go,” she says.

Global Gaming Expo, presented by the American Gaming Association and organized by Reed Exhibitions, returned to Las Vegas in 2021 with attendance of 13,000, down from a peak of 27,000. Some 350 businesses from around the world are exhibiting at G2E, including leading slot manufacturers IGT, Konami, Aristocrat and Aruze Gaming.