by Bob McGlincy

To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, the United States presented a birthday party to the world from Philadelphia. “The 1876 International Exhibition of the Arts, Manufacturers, and Products of the Soil and Mine” showcased American ingenuity, innovation and technology. The celebration promoted patriotism, promised entertainment and was the first modern tradeshow in the United States.

New York, Boston, Cincinnati, Chicago and St. Louis battled for three years for the privilege to host the event. While city leaders argued about hosting the event, politicians, pundits, and members of the press argued the exposition shouldn’t take place at all. The cynics cried it couldn’t be done, complained that it would be too costly, claimed that no one would attend (at least not from overseas), and worried that US products might be viewed as inferior when seen side-by-side with European goods.

Fortunately, the naysayers were proved wrong, and the show was a stunning success. The exposition attracted nearly ten million people at a time when Philadelphia’s population was 817,000. From New Zealand, Norway, North and South America, England, Egypt, India, Istanbul, Australia and Japan, fairgoers flocked to Philadelphia. Outside of Paris, it was the highest attended event of the nineteenth century until the 1893 “World’s Columbian Exposition” took place in Chicago.

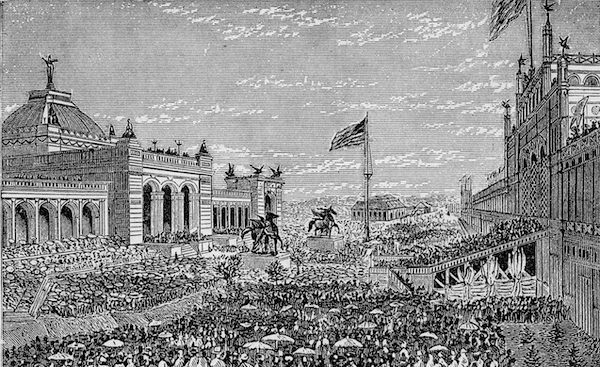

The Fairgrounds were huge. Sprawling across 285 acres in Fairmont Park, it was the largest expanse of land dedicated to a world’s fair at the time. Workers constructed a temporary town of more than 200 buildings, including multiple halls dedicated to machinery, agriculture, horticulture and art. The centerpiece, the “Main Exhibition Building,” enclosed a record-setting 21 acres under one roof. Separate structures were erected for each of the 35 countries exhibiting, and for 26 of the then 37 individual United States; 14,420 businesses occupied 1.9 million square feet of exhibit space. The show was open from May to November, and at a time when the average American wage was $1.21 a day, visitors paid 50 cents for the experience of a lifetime.

Wherever one looked, the Exposition displayed a series of firsts. There were new technologies, new food, new ideas, new products and new sales everywhere.

Emperor Don Pedro of Brazil discovered Alexander Graham Bell’s new invention (“My God, it talks!” he exclaimed while judging the show). Edison debuted his telegraph and electric pen. Remington displayed the first commercial typewriter and charged for souvenir letters. Pratt and Whitney showcased tools manufacturing interchangeable parts, and machine-made fasteners. The Waltham Watch Company demonstrated the first automatic screw-making machine and won a gold medal. HJ Heinz, Charles Hires and Stephen Whitman sold new products (ketchup, root beer and boxed chocolates). Two others making future fortunes selling new food items were J W Tufts and I L Baker (surprisingly popular and profitable, were sales of soda water and sugar popcorn). Bananas were a tasty novelty, while overhead, a steam-powered locomotive moved 60 passengers cushioned in a lavish saloon car. The Wallace-Farmer Dynamo powered three electric arc lights and inspired Thomas Edison; the Grant Difference Engine, a pre-computer, foreshadowed the future. Roebling and Sons exhibited a revolutionary 5¾ inch thick cable (the same cable used in the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge). Krupp unveiled the world’s largest cannon, an 81-tonner. Elsewhere in the hall was a large travel bag that doubled as a portable bathtub (not every new invention on display was successful).

Thanks to Elizabeth Duane Gillespie, the influence and accomplishments of women were recognized for the first time at a World’s Fair: The Women’s Pavilion displayed more than 80 newly patented items, including interlocking bricks, a dishwasher and a cold handle for a hot iron.

The first International Art Exhibition in the US opened at the fair; a separate building presented photographs. The American Library Association originated at the show. Singer, the largest manufacturer in the world, sold multiple models of sewing machines in the main hall, built a corporate pavilion and sponsored the first corporate retreat; they hired six trains in New York and transported 4,000 employees to Philadelphia for an all-expense-paid trip to the Fair.

America was an expanding national marketplace, with shopping an increasingly popular activity. The tradeshow—the first successful B2C and B2B event in the US—turned into a major consumer spectacle, and was the first show where writing orders on the exhibit floor became commonplace. The fair showcased everyday items such as hand tools, furniture, wagons, stoves, fabric, textiles, clothing and lanterns, as well as some less-common ones: Yale locks, Tiffany jewelry, Doulton pottery, Schumacher pianos and suspenders with one’s name custom woven into the fabric. Other items included printing presses, hydraulic and pneumatic power machines, trains, steam engines, dynamos, reapers and windmills. DuPont displayed gunpowder, and arms manufacturers selling new products included Colt, Remington, Smith and Wesson, Gatling, and Krupp.

Organizers of the exposition visited Vienna in 1873 to learn from that fair’s successes and failures. Based on what they learned, the Philadelphia Committee increased railroad and street car service. They built new hotels and offered both high end and inexpensive restaurants. Gardens and fountains dotted the landscape, along with displays and dioramas showing life around the world. And on the outskirts of the Fair, a shanty town sprung up with beer parlors, sideshows, entertainment and can-can dancers.

Built specifically for the Centennial, and stretching to 300 feet in height, the Sawyer Observatory was the tallest structure in the US at the time. It was the tallest exhibit, but not the most popular one. The two most popular and well-attended displays were Liberty’s torch and the Corliss steam engine. Both were 50 feet high.

Lady Liberty’s arm was the first piece of the Statue of Liberty to arrive on America’s shore. For 50 cents, one could climb to the torch balcony and view the fair. The admission fee was designed to be a fundraiser for the base of the future statue. The 1400 horsepower Corliss steam engine, the largest in the world, powered the hundreds of other machines at the show—machines printing newspapers and wallpaper, ones spinning cotton and combing wool, plus others pumping water, sawing logs and making shoes. These dynamic machines simultaneously showcased technology, created sales orders and entertained fairgoers.

The Centennial was a thought-provoking place to see and be seen. Current and future inventors in attendance included George Eastman, George Westinghouse, Moses Farmer, Thomas Edison, Alexander Graham Bell, and a young 16-year-old Elmer Sperry (the “father of modern navigation technology” and inventor of gyroscopic compasses). The show boosted the cross-pollination of ideas and created an incubator for inspiration. More than 10,000 US patents were issued in the first four years after the close of the show!

What was the legacy of America’s first modern tradeshow?

o It sold products, developed businesses and created fortunes.

o It illuminated the dawn of a new American manufacturing age.

o It displayed the country’s industrial power and future potential.

o It launched 27 major expos in the US over the next 28 years (including world fairs in Chicago, Buffalo and St Louis).

o It transformed the global image of the United States.

Philadelphia’s Centennial Exposition brought people, money, ideas and businesses together. It unfurled a blueprint for the future, and proved exhibitions and tradeshows work.