by Bob McGlincy, The Tradeshow Times

by Bob McGlincy, The Tradeshow Times

Imagine having less than a year to produce the world’s largest tradeshow … but first, you have to build the convention center.

London’s Crystal Palace (pictured above) was a unique iron and glass structure. Four times larger than anything in the world at the time, it covered 19 acres of land, provided 900,000 square feet for exhibits, and enclosed 33,000,000 cubic feet of space. Despite its massive size, the construction was an “I&D” project: it was designed as a temporary structure; it was partially pre-fabricated; it was installed on site; it had tight time constraints; it had to be completed before show opening; it was dismantled after the show, shipped to a new location, and then rebuilt in a different configuration.

This huge structure was specifically planned and constructed to house “The Great Exhibition of 1851.”

As the world’s first international exposition, the show hosted 14,000 exhibitors from 44 countries, and attracted over 6 million paid attendees in five and a half months. Designed to showcase technology and establish Great Britain as an industrial leader, the exhibition is considered to be “the first modern tradeshow.”

In hindsight, the success of the show seems almost inevitable. It was not. At one year prior to show opening—despite the exposition having been announced, and invitations sent—there was no design, no land and only limited funding for the event. The Executive Building Committee tentatively approved Joseph Paxton’s innovative design on July 15, and a verbal contract for construction was agreed to on Friday, July 26, 1850 (the contract would not be signed until October). The following Tuesday—nine months and two days prior to show opening—30 workers entered Hyde Park to layout the project.

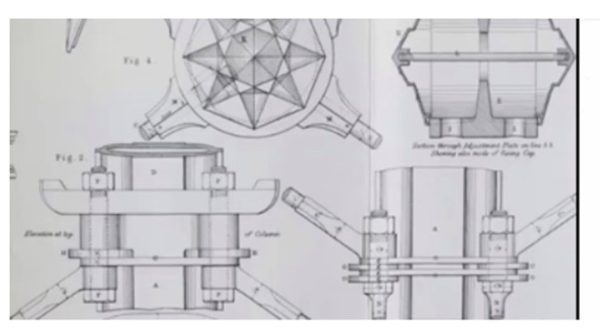

The size, number and type of materials needed for this herculean build was staggering. A partial list includes:

- 10 million pounds of iron

- 720,000 feet of lumber

- 202 miles of sash bar

- 30 miles of gutters

- 3,230 iron columns

- 2,224 trellis girders

- 293,653 panes of glass

Materials had to be transported by train to London, loaded onto horse drawn wagons, hauled to the construction site at Hyde Park, and unloaded—all before any visible progress was evident.

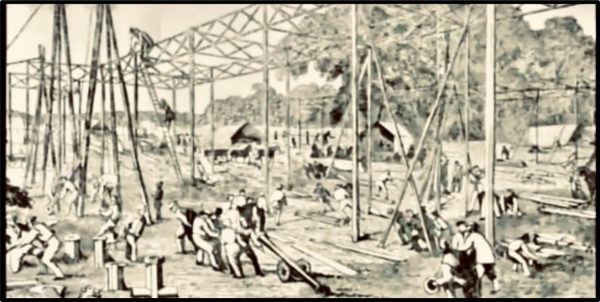

Work began at the end of July, 1850. On July 30, the crew marked the ground, and plotted locations for the column bases. The building would be 1,848’ x 408’. The highest interior section would be 128’, tall enough so existing trees within the planned layout would not have to be cut, or removed. For the next nine months, crews worked every day, Monday through Saturday, until the show opened on May 1, 1851. (Work could not be performed on Sundays in Victorian England).

Laborers, iron workers, glaziers, carpenters and painters were all needed at different times. Strictly controlling tasks and labor numbers was critical to reining in the cost of the build. The daily labor call fluctuated, based on the amount of work possible in a given week. The crew size increased from 30 that first day in July to more than 2,000 men a day in November; it dropped to 1,417 the last week in January and increased to 2,128 men a day in the beginning of April.

Not all shows in the 19th century opened on-time or on budget, but this one did; and it made a substantial profit. After the show closed in October, the two individuals most responsible for designing and building the Crystal Palace, Joseph Paxton and Charles Fox, received knighthoods. Paxton also collected a bonus equivalent to almost a million dollars in today’s money ($969,848).

The Crystal Palace is the biggest I&D project in history for several reasons: it was big in terms of size (33 million cubic feet); it was big in terms of time (it took seven months, working six days a week, to build the basic structure); it was the big in terms of labor (2,000+ temporary workers every day for months); but most importantly, it was huge in terms of significance—the show was a defining moment in the Industrial Revolution, and the structure inspired hundreds of future venues. In time, other projects would be larger. And some, a few, would be temporary—but none were dismantled and re-installed in a different location, except for the Crystal Palace. And none would be as historically significant.

Kudos to all the I&D and other show-site workers who toil tirelessly behind the scenes to make the magic of tradeshows happen.

A version of this story originally appeared in the Nov./Dec. 2021 issue of Exhibit City News, p. 14. For original layout, visit https://issuu.com/exhibitcitynews/docs/ecn_nov-dec_2021

![]() Bob McGlincy is director, business management at Willwork. Willwork creates engaging, energized, and exceptional event experiences. He can be contacted at Bob.McGlincy@willwork.com.

Bob McGlincy is director, business management at Willwork. Willwork creates engaging, energized, and exceptional event experiences. He can be contacted at Bob.McGlincy@willwork.com.