by Bob McGlincy, director, business management at Willwork Global Event Services

Wherever there are crowds, there is the possibility to sell products and to make money. This face-to-face opportunity is one of the common threads linking fairs, expositions and tradeshows.

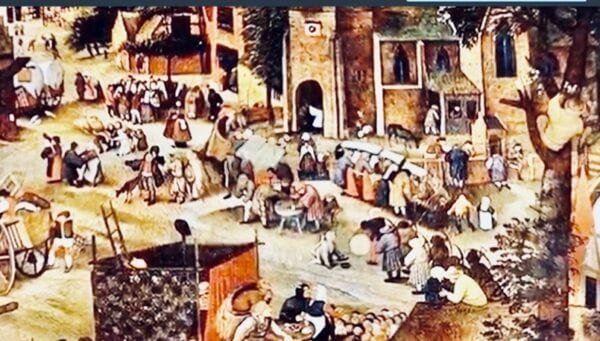

Tradeshows are not a new phenomenon. At their most basic, tradeshows are a gathering of people, ideally both buyers and sellers, in the same place and at the same time. By this definition, such happenings have been occurring in marketplaces for thousands of years: from Middle Eastern bazaars located outside city walls selling a variety of wares as far back as 3000 B.C., to street vendors in Athens and Rome before the time of Christ, to roaming caravans of merchants during the Middle Ages—all looking to sell, trade, and buy goods and services—these were the initial forerunners to modern day tradeshows.

The word “fair,” derived from the Latin, “feria,” means a holy day or religious festival. The Champagne Fairs originated as livestock and agricultural events, and traveled to different towns in northeastern France during the 12th and 13th centuries. They evolved into six celebrations a year, usually centering on religious dates, and lasting a month or longer. Selling animal skins, fur, leather, spices, textiles and other merchandise, they attracted large crowds. These fairs were one of the first examples of a linked European economy; they began to diminish in the late 1400s, as major commercial hubs developed permanent markets.

The first recorded trade fair in Europe, located in a single town, was in Frankfurt, Germany. First documented in 1150, it became official, and legally recognized, in 1240 after Emperor Frederick II granted a license, or “privilege” to hold the fair. This annual event, known as the Autumn Fair, was followed with a Spring Fair in 1330. In 1365, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV, desirous of establishing new trade routes, granted a trade fair license to Hamburg.

The first “Christmas Market” may have been in Dresden in 1434, although earlier “December Markets” were held in Vienna and Munich, in 1298 and 1310, respectively. And not to be outdone by other regions, Frankfurt instituted a December Market in 1393, adding to their existing Spring and Autumn Fairs. In addition to traveling merchants, these fairs attracted entertainers: jugglers, acrobats, troubadours and, occasionally, a trained bear. Local bakers and cooks would also set up tables.

Frankfurt holds the record for the first trade fair, and also for the oldest tradeshow, one in

existence for more than 550 years. The Frankfurt Book Fair officially dates back to 1462, and reportedly had 40,000 visitors that year. Today, that same show is considered to be the biggest book fair in the world, in terms of number of attendees, publishers and exhibiting companies. In 2019, the show ran for five days, and attracted 7,300 exhibitors and 286,000 attendees. Book Fairs in Kolkata and Cairo have recorded significantly larger numbers of visitors, but are judged to be a different type of event.

Fairs were not exclusive to the continent of Europe. In 1204, King John of England licensed an agricultural fair in Ireland. Located in the south side of Dublin, in the district of Domhnach Broc (“The Church of Saint Broc”), the “Donnybrook Fair” lasted for more than 650 years. By the late 1700s, it became more of a carnival, and gained a reputation for drinking, fighting and “hasty marriages.” The phrase donnybrook, meaning a brawl or argument, lived on even after the fair was disbanded in 1866.

Between 1608 and 1814, there were a series of “Frost Fairs” in London, whenever the river Thames froze over. Activities included dancing, football, ice skating, sledding, puppet plays, horse racing, coach rides, bull baiting, fox hunting, ox roasting, elephant walking, ice fishing and nine pin bowling. Barbers, shoemakers, fruit sellers, tavern keepers, pub owners and other tradespeople set up tents and booths to peddle their wares. There were hot food stands, tobacco stands, pubs, brothels and even printers selling personalized certificates of attendance. Fires, food and drink were plentiful. The last “Frost Fair” commenced on December 27, 1813. The ice began breaking up unexpectedly on Feb. 5, 1814; several people drowned, but the Fair continued for another two days, ending on the seventh. Munich’s first Oktoberfest dates back to this same period, originating with Prince Ludwig’s wedding in 1810, and expanding on a regular basis in 1818.

There are many precursors to the modern day convention, ranging from agrarian and early industrialized events, to local and state festivals, to “world” fairs and expositions. They evolved sharing several common attributes: part community—a gathering of people, usually having a good time; part education—an offer of learning or speeches; part demonstration—new products and/or technologies; part brand awareness (religious or secular); part entertainment; and almost always part sales oriented, and economy driven (even if many of the opportunities were not immediate ones).

Early Industrial Expositions and Fairs, 1798–1849

The focus of emerging trade exhibitions is on Europe, and to a lesser degree, America, because Europe is where the Industrial Revolution began. It was industries, and the need to promote and sell product, that propelled these shows. There were at least 30 expositions in the first half century, and that number increased more than eight-fold, in the second half of the nineteenth century.

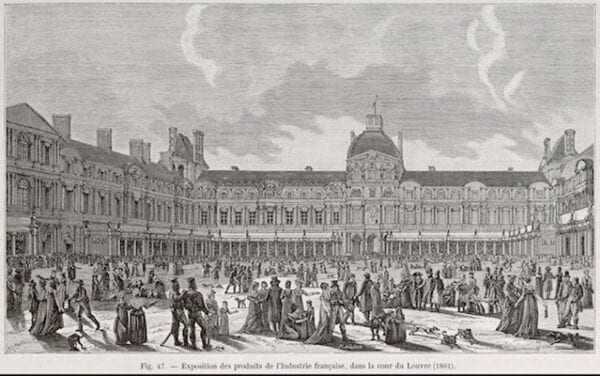

Although there were minor industrial meetings in Genoa in 1789, and Hamburg in 1790, the first industrial exhibition was in Prague, in 1791, at the coronation of Leopold II. The first public show, the “L’Expostion Publique des Produits de L’industrie Francaise” was in Paris in 1798; and it would prove to be the first of 11 French industrial expositions, held between 1798 and 1849. They were intended as celebrations, and designed to promote French products. Only, and exclusively, French products: If it wasn’t made in France, it could not be displayed at any of the Expositions.

The first Paris exposition showcased 110 exhibitors. This number doubled in 1801, and increased to 540 exhibitors in 1802. The fourth exposition in 1806 had 1,422 exhibitors. Political and military events delayed the next show until 1819. That show and the next two, held in 1823 and 1827, had between 1,642 and 1,695 exhibitors. Clearly, interest from exhibitors and attendees was steadily increasing. The 1827 show attracted 600,000 visitors in 60 days.

The first Paris exposition showcased 110 exhibitors. This number doubled in 1801, and increased to 540 exhibitors in 1802. The fourth exposition in 1806 had 1,422 exhibitors. Political and military events delayed the next show until 1819. That show and the next two, held in 1823 and 1827, had between 1,642 and 1,695 exhibitors. Clearly, interest from exhibitors and attendees was steadily increasing. The 1827 show attracted 600,000 visitors in 60 days.

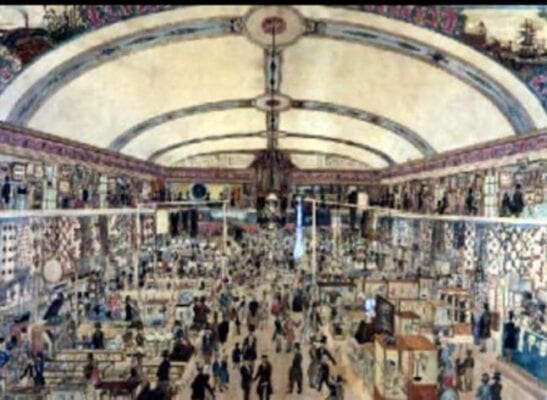

The Paris Exposition planned for 1832 had to be cancelled due to local mobs rioting (think Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables). That same year, a cholera epidemic killed 2.5 percent of the entire population of Paris. Shows were held in 1834 and 1839, and continued to increase in size. The tenth Exposition in 1844, restricted the number of exhibitors; yet it still set a record with 3,960 exhibitors.

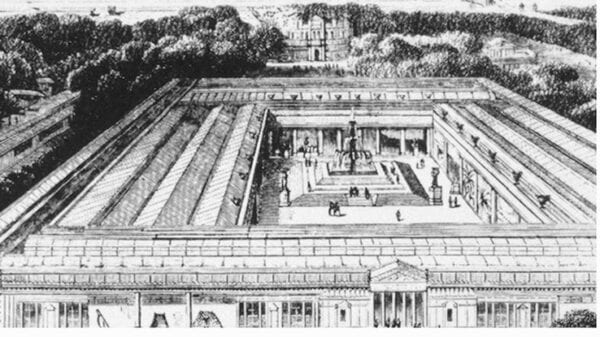

A new display hall of 240,000 square feet was built for the 11th Exposition, held in 1849. A record 5,494 exhibitors participated, necessitating separate buildings to house the overflow exhibitors and the larger machinery. The show is known for its photographic displays.

The 1844 Exposition is credited as the inspiration and motivation for Prince Alpert, and Great Britain, in the planning and financing the Great Exhibition of 1851.

The Paris expositions are also credited as the basis for the five Turin industrial expositions from 1829-1850, the three in London in 1847, 1848 and 1849, as well as the Expositions in Bern and Madrid in 1845, Genoa in 1846, Brussels and Barcelona in 1847, St Petersburg in 1848, and the 1849 Expositions in Lisbon and Birmingham. Berlin hosted three industrial expositions. The first, in 1822, lasted for one and a half months; it had 182 exhibiting companies displaying 998 products, and attracted 9,514 visitors. The second was in 1827, and the third was in 1844—that one had 3,040 exhibitors “displaying a large variety of German industrial goods” and registered 260,000 attendees.

The steady growth and popularity of these shows clearly indicates a need for them, and foreshadows the popularity of tradeshows and convention centers in the United States and Europe in the twentieth century.

Looking across the Atlantic, there was nothing as grand. The first agricultural fair in North America prior to 1800, occurred in 1765 in Windsor, Nova Scotia, although the first community fair may have been in Hardwick, Mass., in 1762. The first county fair in the U.S. was a “cattle show” in 1810 in Pittsfield, Mass., initiated by Elkanah Watson, who first brought two sheep to show in the Park Square in 1807. By 1811, the fair was a competition; it had a sheep shearing demonstration, and offered prize money of $700; animals included 383 sheep, 109 oxen, 9 cows, 7 bulls, and 1 boar. By 1818, the fair included a plowing competition.

The American Institute Fair, launched in New York City in 1829, attracted 30,000 people, and continued as an annual event until 1897. It was founded “for the encouragement of agriculture, commerce, manufactures and the arts.” Considered by some to be the first world’s fair in the U.S., it did not attract the crowds that the expositions in Europe did. Most consider the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia to be the first “official” world’s fair in the U.S., although some bestow that honor on the New York 1853 exposition.

The first state fair was “The Great New York State Fair” Sept. 29-30, 1841. By various accounts, it attracted between 10,000 and 15,000 people. Events included speeches, animal exhibits, a plowing contest and samples of manufactured goods for both the farm and the home—and, of course, there was food and alcohol. In 1849, an attraction was added: a 50-foot-tall, manually-powered oak and iron wheel with wooden buckets that could hold adults or children; it was a forerunner to the Ferris wheel which premiered at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. The second state fair in the U.S. was in Michigan in 1849, and the third opened in Ca lifornia in 1851, the same year as what is generally recognized as the first modern tradeshow.

lifornia in 1851, the same year as what is generally recognized as the first modern tradeshow.

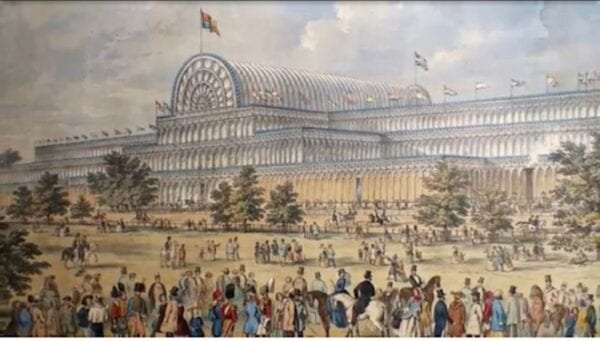

“The Great Exhibition” in London in 1851 was aptly named—it had more than 100,000 exhibits, and attracted more than 6,000,000 paid attendees in five and a half months. See previous columns for that story.

During the first half of the nineteenth century, from Barcelona to Brussels, from Berlin to Bern, from France to Russia, and from Italy to England—no matter what city or what country—all of the European expositions were provincial events, displaying only “home-country” products. This was about to change. And with this change, the exposition industry would never be the same again.

Bob McGlincy is director, business management at Willwork Global Event Services. He can be contacted at Bob.McGlincy@willwork.com. Willwork creates engaging, energized, and exceptional event experiences.