Tradeshows promote technology, display new products, popularize new brands, and occasionally even showcase new foods. They have been doing this for the past 170 years.

The Great Exhibition in London in 1851 is considered “the first modern exhibition” and has been detailed in a previous column. After that show, expositions traveled across the water to Ireland and America, then back across the Atlantic to London, Paris, and other major commercial centers in Europe.

The Great Exhibition in London in 1851 is considered “the first modern exhibition” and has been detailed in a previous column. After that show, expositions traveled across the water to Ireland and America, then back across the Atlantic to London, Paris, and other major commercial centers in Europe.

Some new products displayed during that quarter century included: the telephone; the typewriter; the sewing machine; the passenger elevator; plastic; vulcanized rubber; submarine communication cables; reinforced concrete; the Colt revolver; the repeating rifle; the Gaitling gun; and the first elevated train. Some newly promoted foods included: Heinz ketchup; Hires root beer; sugar popcorn; soda water; ice cream sodas; and the first bananas in North America. Entrepreneurs and companies that made a name for themselves included: Singer, Krupp, Colt, Edison, Westinghouse, Bell, Remington, Goodyear, McCormick, Otis, J. P. Lippincott, Smith & Wesson, Pratt & Whitney and Yale Lock.

Many countries tried to imitate the Great Exhibition. Few did it as well; and none in this period were profitable. Many new exhibition halls were iron and glass builds, similar to London’s Crystal Palace, although designed to be permanent. Three immediate examples were in Dublin and New York in 1853, and in Munich in 1854.

The list of expositions below is not all inclusive (there were more than 240 shows between 1851 and 1901), but is intended highlight some of the major ones, based on size, location, timing and/or technology displayed.

1852: The Irish Industrial Exhibition of 1852 opened in Cork a year after The Great Exhibition. Taking place two years after the Great Famine, the fair was intended to revive local industries for whiskey, slate, gingham and hydraulic presses. There was also a hall dedicated to the fine arts. It attracted only 129,000 people.

1853: The Dublin show attracted 1.15 million visitors, including Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. William Dargan, a developer of the Irish railways, donated $400,000 for this show in order to introduce the Industrial Revolution to Ireland. Several elements of the interior London design were incorporated into this hall. Despite the donation and the design, Dublin could not duplicate London’s magic. The show lost the equivalent of a million dollars.

1853: The Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations in New York City also attempted to duplicate the Great Exhibition. Despite having its own Crystal Palace, and running for 16 months, it was unsuccessful. It is remembered for four things: the debut of the Otis elevator; attracting (only) a million visitors; losing money; and being the first show to allow sales directly from the show floor (that was during the second year, in an effort to boost interest).

1853: The Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations in New York City also attempted to duplicate the Great Exhibition. Despite having its own Crystal Palace, and running for 16 months, it was unsuccessful. It is remembered for four things: the debut of the Otis elevator; attracting (only) a million visitors; losing money; and being the first show to allow sales directly from the show floor (that was during the second year, in an effort to boost interest).

The show opened two and a half months behind schedule. And even then, the buildings were not complete. The delays were caused by the Commission members and the architects arguing over designs and cost overruns. Partially due to the delayed opening, only 600,000 people attended the show in 1853. To boost attendance, the show was extended. P. T. Barnum was hired to attract celebrities, and promote new products and exhibits. He paid Elisha Otis $100 to demonstrate an elevator safety brake: Otis raised a platform 20 feet in the air, shouted to attendees below, “Should I cut the cable?” And that was the start of passenger elevators, and the future of high rise construction.

1854: The Glaspalast in Munich was another iron and glass Crystal Palace inspiration. Again, there are similarities with both the interior and exterior look. It was smaller, 768 feet long, 220 feet wide and 82 feet high, with 37,000 windows. It was built to house “The First General German Industry Exhibition” (pictured left). Prior to the opening of the show on July 15, there was cholera outbreak, but the show did not close. Opening day attendance was 90,000.

1855: Emperor Napoleon III and others in France were upset that the British had taken France’s idea of an industrial exposition, and made it better. They wanted to outdo England. They came close with 5.1 million attendees and businesses from 27 different companies. But having failed to beat Britain this time, they would try four more times, between 1867 and 1900, attracting crowds from 12 to 50 million.

This year was the first time a French exposition would charge admission. The show lasted six months and was known for its works of arts, including photography, but not for innovative technology. It developed the significant “Bordeaux Wine Official Classification,” and displayed a 10-foot-high percolator that brewed 2,000 cups of coffee an hour.

One novelty at this expo: price tags. Displayed items could be purchased on the spot—or ordered for later delivery. It’s estimated the Fair lost about $4.5 million. But money was spent on hotels, restaurants, the theater—and of course, on the items purchased on the show floor.

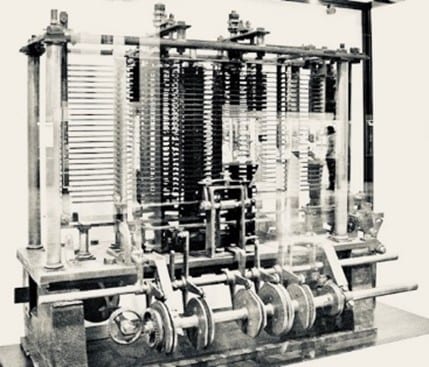

1862: London came close to matching the 1851 show, with 6 million visitors and exhibitors from 39 countries. New inventions included: the electric telegraph, submarine communication cables, plastic and Babbage’s analytical engine—the precursor to the modern computer (pictured right). The machine was built from plans displayed at the show, plans Babbage was prohibited from presenting at the Great Exhibition 11 years earlier.

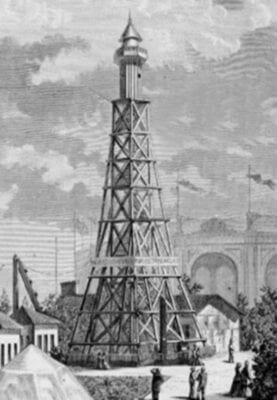

1867: 15 million visitors and 50,226 exhibitors from 42 countries came to Paris. This Expo brought a carnival atmosphere to the city, with its activities in the park. Previous expos had been more serious; this one was the first to have restaurants and amusements outside, ringing the main building. New inventions included reinforced concrete, an electrical tower (the English Lighthouse, pictured left), and a hydrochronmter (a water clock) which is still working today. Bonds to finance the Suez canal were sold from a display at the show.

1871 & 1872 were two uninspiring years for expositions, possibly due to the smallpox pandemic. Still, people traveled. London attracted 1,142,159 visitors, from 35 countries at their show. Moscow had 750,000 visitors and more than 12,000 exhibitors.

1873: This was still not a good year: smallpox was lingering; cholera was spreading; and the financial panic of ’73 triggered a depression in both Europe and North America. Nevertheless, Vienna engaged more than 7 million visitors and attracted 42,584 businesses from 35 countries. 643 businesses exhibited from the U.S. Despite the crowds, the show lost $9 million.

Philadelphia sent a delegation to observe the show in advance of their own exhibition: they wanted to learn from Vienna’s successes a nd mistakes, and determined to improve and increase both transportation and lodging, and to lower overall costs.

nd mistakes, and determined to improve and increase both transportation and lodging, and to lower overall costs.

1876: Philadelphia saw 10 million visitors and 14,420 exhibitors from 35 countries. Prominent displays included: Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone; Remington’s typewriter; an electric pen, Krupp’s cannons; Edison’s telegraph; screw cutting machines; Heinz ketchup; Hires root beer, sugar popcorn, the first bananas in North America and the Centennial Monorail. The Main Exhibition Building (pictured right), with a total enclosed area of 21.5 acres, was the largest building in the world at that time. Philadelphia set new records for opening day attendance, and also for single day attendance of a quarter million on October 9. Excluding shows in Paris, Philadelphia had the largest total crowds of any Exposition between 1851-1892.

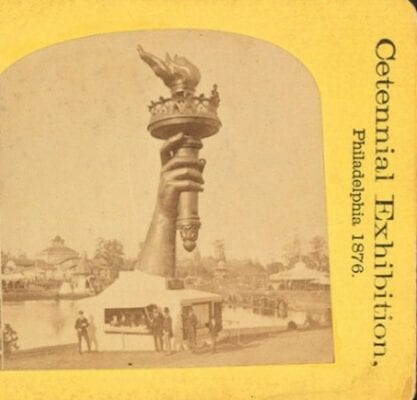

The right arm and torch of the Statue of Liberty was first displayed at the Philadelphia Exposition (pictured left). For 50 cents, one could climb to the balcony and survey the show. The admission fees were later used to fund the statue’s pedestal. The Statue of Liberty’s head was displayed in Paris 1878, before the full statue’s arrival (in multiple pieces) in New York in 1886.

The right arm and torch of the Statue of Liberty was first displayed at the Philadelphia Exposition (pictured left). For 50 cents, one could climb to the balcony and survey the show. The admission fees were later used to fund the statue’s pedestal. The Statue of Liberty’s head was displayed in Paris 1878, before the full statue’s arrival (in multiple pieces) in New York in 1886.

The Centennial Exposition was the first official world’s fair in the U.S. It was also the first show to write sales orders on the tradeshow floor. Tradeshows work. In addition to showcasing new products, and new technology, tradeshows also showcase new foods. Some lasted; some didn’t. One that lasted was Hires root beer. Created by Charles Elmer Hires, a pharmacist in Philadelphia, he came up with idea while on his honeymoon in 1875. He paid for a show sponsorship, and began giving away free glasses of his special root beer. He first sold it as a concentrate of 16 different roots, barks, herbs and berries; then in 1884, he started producing a liquid extract and syrup for use in soda fountains. After incorporating, he started supplying Hires in small bottles, and sold more than a million units in 1891. In 1909, soda fountains in the U.S. served more than 65 million glasses of his root beer. Hires believed in promoting his product: both at tradeshows, and through advertising. He was quoted as saying, “Doing business without advertising is like winking at a girl in the dark. YOU know what you are doing, but nobody ELSE does.” In 1960, the Hires family sold the company to Consolidated Foods.

Tradeshows make a difference. They create jobs, display inventions and sell products. It has happened in the past, and it will happen in the future. It is time, past time actually, to return to the business of tradeshows.

![]() Bob McGlincy is director, business management at Willwork Global Event Services. Willwork creates engaging, energized, and exceptional event experiences. He can be contacted at Bob.McGlincy@willwork.com.

Bob McGlincy is director, business management at Willwork Global Event Services. Willwork creates engaging, energized, and exceptional event experiences. He can be contacted at Bob.McGlincy@willwork.com.