by Bob McGlincy, director, business management at Willwork Global Event Services

“Those who are so fortunate to see it hardly know what most to admire. Around them, amidst them, above their heads, was all that was beautiful and useful in nature and in art. Above them rose a glittering arch, far more lofty and spacious than even our noblest cathedrals.” London Times, May 2, 1851.

Queen Victoria opened this first international exposition on May 1, 1851. She was accompanied by her husband, two children, and 25,000 VIPs who paid a premium for the privilege to be there on day one. Estimates of the size of the crowd standing outside varied from 300,000 to 500,000.

On day two, the show opened to the public, and 16,560 paid to enter the building. Word of mouth increased attendance. On October 9, 109,915 paid to view the Exhibition (probably not the best day to walk the floor and tour the show). The show attracted more than 6,000,000 attendees—more than a third of the entire population of England at the time.

So what was the show like? Why did so many people choose to visit?

What would one see walking the floor?

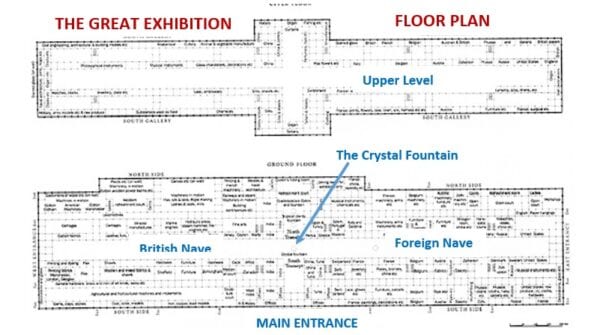

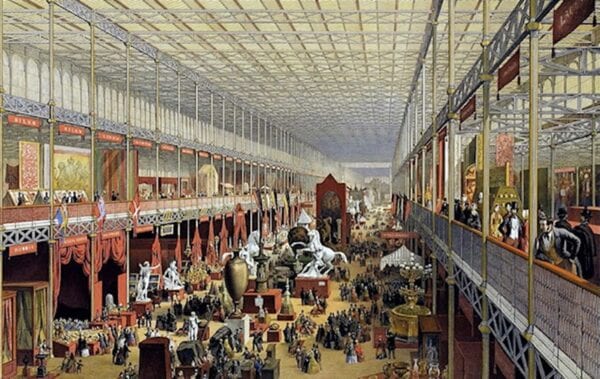

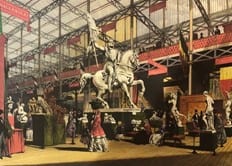

Visitors to the Exhibition first passed through a turnstile at the main entrance. The largest fountain, and one of the elms was directly ahead. Before arriving at the fountain, and the main exhibit areas, there were pavilions on either side. From the left, fragrant smells of colonial produce from Trinidad assaulted the senses; and on the right, tents from Tunis displayed skins of leopards and lions. The British area, including India, Canada and other colonies, was to the left of the fountain; and the foreign exhibitors were to the right. The United States pavilion was at the end of the foreign nave. Beyond the fountain were more exhibit areas, refreshment stands and comfort stations.

Do not be deceived by the small size of the floor plan—the building was more than one-third of a mile long!

Do not be deceived by the small size of the floor plan—the building was more than one-third of a mile long!

Exhibits were on two levels, but most of the major displays were on the ground floor. There were 14,000 exhibitors (almost half from counties other than Britain), and more than 100,000 exhibits. A total of 44 countries had their own display areas, including, Great Britain, France, Germany, Russia, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Switzerland, Sweden, China, India, Turkey, Holland, Canada and the U.S. Great Britain occupied half the exhibit hall; after that, France, and then the U.S. had the largest display areas.

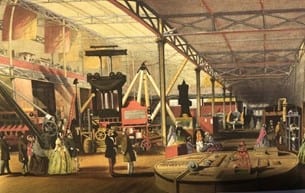

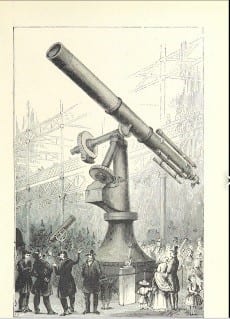

Technology and working equipment were popular. Exhibited items at the show included ironwork, firearms, furniture, fabrics, tinned food, steam engines, locomotives, hydraulic presses, printing presses, telescopes, pianos, an electric telegraph, a reaping machine, microscopes, a telegraph, vulcanized rubber, the first voting machine, musical and surgical instruments, as well as the precursor to the fax machine.

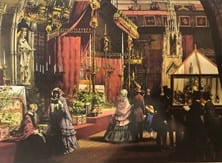

Walking into the British Nave, there were pavilions from India on both the left and right side, followed by displays from other colonies, before arriving

at British products and technology. In addition to the pavilions, there was a hall of agricultural equipment and two halls of machinery. There were displays of linens, cotton, flax, furs, woolens, perfume, pottery, porcelain, hardware, furniture, machinery and equipment. There was a folding piano, an expanding hearse, a waterproof watch and a locomotive so big that it required 22 horses to drag it into place.

A printing press produced a thousand copies of the London Times in one hour.

There was a voting machine, an envelope folding machine that also glued the envelopes and a cigarette machine. There were artificial teeth made out of hippopotamus, as well as teeth that could swivel so the user could yawn.

There was a hydraulic press where one man could move thousands of pounds of iron. There was a bed with a timer that would

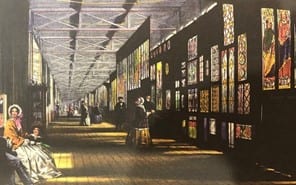

stand the sleeper upright. A revolutionary lens for lighthouses, and a carriage drawn by kites were also highlights. Upstairs, there were medicines, surgical tools, musical instruments, embroidery, more linens, toys and the gallery of stained glass. Leaving the upstairs, visitors could pass through several Fine Art Courts, on the way back to the the Crystal Fountain and onto the Foreign Nave.

The Koh-I-Noor diamond (186 carats) attracted large crowds. Other showstopping displays were “the giant telescope,” and a cotton production demonstration moving from spinning cotton to finished cloth. The show had the first public toilets which charged the users a penny. Thomas Cook helped move crowds to London, and the first America’s Cup competition was held in conjunction with the show.

The Koh-I-Noor diamond (186 carats) attracted large crowds. Other showstopping displays were “the giant telescope,” and a cotton production demonstration moving from spinning cotton to finished cloth. The show had the first public toilets which charged the users a penny. Thomas Cook helped move crowds to London, and the first America’s Cup competition was held in conjunction with the show.

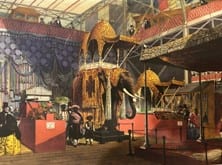

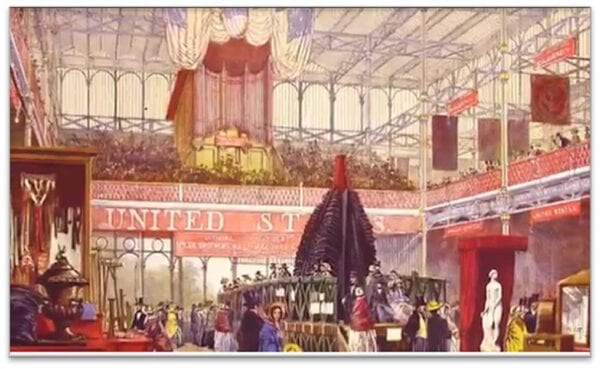

At the far end of the Foreign Nave, was the U.S. area, or the American Pavilion Display; it was the third largest exhibit area on the floor. Unfortunately, there was so much empty space that Punch magazine joked, the Americans should rent space as a bed and breakfast, or use it as an additional waiting room for the toilets. The show did not charge for exhibit space, and the anticipated number of American entries did not materialize. Unlike many of the countries, the U.S. did not sponsor or pay for the delegation in any way. The exhibitors’ shipping costs were donated, and they were fortunate that upon arrival in London an American banker, George Peabody, paid to have the exhibit properties unloaded and transported to the hall.

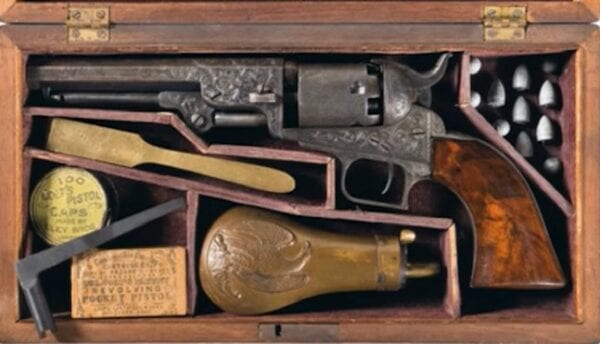

Major U.S. product displays included Cyrus McCormick’s Virginia grain reaper (which modernized harvesting and was the foundation of the International Harvester Company); Charles Goodyear’s revolutionary vulcanized rubber (the large display in the middle of the photo above); I. M. Singer’s sewing machine (Singer manufactured the first straight stitch sewing machine in Boston in 1850); a collection of daguerreotypes by Mathew Brady; a patented double grand piano for four pianists; a cotton gin; Cincinnati pickles; Virginia honey; and Samuel Colt’s “formidable revolving charge pistols.” And, of course, no area in the hall would be complete without at least one marble nude (“The Greek Slave” by Hiram Powers).

According to English novelist and poet Charlotte Brontë, ““It is a wonderful place … vast, strange, new and impossible to describe. Its grandeur does not consist of one thing, but in the unique assemblage of all things. Whatever human industry has created you find there. … It seems as if only magic could have gathered this mass of wealth from all the ends of the earth.”

The Great Exhibition was a huge success, viewed from any vantage point. Biggest. Monumental. Historic. Trend setting. Profitable. It laid the ground work for the design, concept and function of future tradeshows. It became one of the defining points of the 19th century. And despite initial fears, it was a peaceful event.

The Great Exhibition was a huge success, viewed from any vantage point. Biggest. Monumental. Historic. Trend setting. Profitable. It laid the ground work for the design, concept and function of future tradeshows. It became one of the defining points of the 19th century. And despite initial fears, it was a peaceful event.

The show excelled and set records in terms of numbers of attendees, exhibitors and square feet of exhibit space. Perhaps most impressive, it made a profit. It didn’t just cover the operating expenses, it made 186,000 pounds. Today, that would be the equivalent of more than $21 million. Now, that’s a successful show!

Was the show a success from an individual or company sales standpoint? Hard to say. The show wasn’t designed to write orders, but rather to display technology, and sell product at a later date. Prices could not be displayed, but exhibitors were allowed to discuss price, if asked. Except for the three sponsored refreshment centers, no sales were allowed on the show floor, although there were myriad vendors selling souvenirs and food in Hyde Park. Still, there were individuals and companies that made a name for themselves: Americans Brady, Colt, Goodyear, McCormick and Singer are a few easy examples. Alfred Krupp is another entrepreneur who benefited from exhibiting at the show: he displayed a solid steel, flawless ingot weighing 4,300 pounds, and his first steel cannon (a six pounder); Krupp was just getting started exhibiting at expositions, and building his munitions business.

The power of trade shows: As part of the US delegation, Samuel Colt traveled to London for the Exhibition to present a firearms display and demo. He owned a manufacturing company in Hartford, Conn., named the “Colt Armory.” Long before the assembly lines of H. J. Heinz or Henry Ford, Colt’s factory utilized a production line to assemble interchangeable parts. At the Exhibition, Colt displayed his repeating revolvers. Attracting crowds with a live demonstration, he disassembled ten revolvers, and then reassembled them using parts from different guns. He delivered a lecture on mass production techniques to the Institute of Civil Engineering. Colt was the first U.S. Company to open a branch overseas; he built a factory in London in 1852, and sold 23,000 revolvers to the British Army and Navy. (Pictured here is a Colt “show floor giveaway” provided to Prince Albert and other distinguished attendees).

After May 1, the show was open for 140 days; it was closed on Sundays. Queen Victoria enjoyed the show so much, she returned 40 more times. After the show closed to the public, it remained open for three more days. The first two were for exhibitors and their families only. And day three was for the closing ceremonies.

In addition to making a massive profit, The Great Exhibition birthed the modern tradeshow industry, and inspired at least 240 additional shows during the second half of the century. They showed others a blueprint of how to make it work. Immediate examples were: The Cork Exhibition of 1852; the Dublin Exhibition of 1853; the New York Exhibition of 1853; and the Munich Exhibition of 1854. The last three all had their own imitation Crystal Palaces. The number of shows steadily increased each decade: (15) expositions in the 1850s; (27) in the 1860s; (44) in the 1870s; (82) in the 1880s; until a slight decrease to (72) exhibitions in the 1890s.

The reason for this tremendous and fantastic growth in the number of shows should be obvious: exhibitions work and they work very well. It made political and economic sense for other cities and countries to follow London’s lead. If a city could attract a million, or ten million visitors, then it had millions of opportunities to sell ideas and promote products—in other words, potentially millions of opportunities to make money.

Bob McGlincy is director, business management at Willwork Global Event Services. He can be contacted at Bob.McGlincy@willwork.com Willwork creates engaging, energized, and exceptional event experiences.